ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Hilde Weisert's 2015 poetry collection, The Scheme of Things, was published by David Robert Books. Her poems have appeared in such magazines as The Cincinnati Review, Prairie Schooner, Southern Poetry Review, and Ms. Awards include fellowships from the NJ State Council on the Arts and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the 2008 Lois Cranston Poetry Prize, and recent honorable mentions in the Allen Ginsberg Poetry Awards, the Robert Frost Foundation Award, and the New Millennium Writings Contest. Her poem, "The Pity of It," was winner of the 2016 Tiferet Journal Poetry Award. With Dr. Elizabeth Stone, she is co-editor of the anthology, Animal Companions, Animal Doctors, Animal People: Poems essays, and stories on our essential connections, published by the Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, 2012. She lives in Sandisfield, Massachusetts and Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

June 22, 2017

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

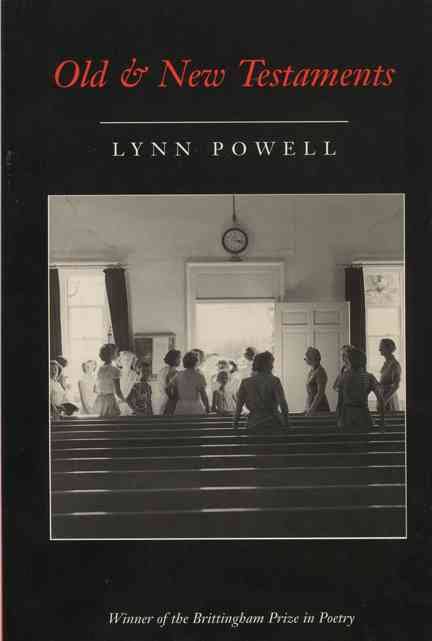

Review of Old & New Testaments by Lynn Powell

Old & New Testaments

by Lynn Powell

University of Wisconsin Press, 1995

When friends of mine were arguing recently about whether to raise their new baby with or without a conventional religious education, I gave them Lynn Powell's Old & New Testaments (University of Wisconsin Press, 1995). In Powell's hands, the Bible stories and verses, mysteries and perils learned in childhood become a vital myth that colors and deepens almost every aspect of daily life, for both the child and the adult she becomes. One is tempted to conclude that the conditions of a Baptist upbringing are necessary and sufficient to make a poet — that this is the school all poets should go to. Of course, the material is well served by the observant imagination of the child Powell was and the keen intelligence, humor, and sure-footed craft of the adult poet who has clearly found her metier.

Powell's book, winner of the 1995 Brittingham Prize in Poetry, is organized in four parts representing the Old and New Testaments of the title, but not in the expected order: Genesis, Song of Solomon, Revelation, and Job — the beginning, the idyllic time, the end, and finally, returning to the Old Testament's most timeless book, Job, the existential present.

Each part begins with a biblical passage that gives a good indication of what Bible we are talking about and what world we are about to enter. From Genesis:

And he said, I will surely return to you at this time next year;

and behold, Sarah your wife shall have a son.

And Sarah was listening at the tent door …

and Sarah laughed to herself …

From Song of Solomon, there is sensuous desire (for the "garden [that] breathes out fragrance, its spices wafted above", for the beloved to "come into his garden and eat its choice fruits"); from Revelation, the sting of surprise in finding the little book "in my mouth, sweet as honey; but when I had eaten it, my stomach was made bitter;" and from Job, the question:

Where is the way to the dwelling of light?

And darkness, where is its place,

that you may take it to its territory

and that you may discern the paths to its home?

This is a richly physical, natural world full of the apparent opposites of the sweet and bitter, light and dark, as well as laughter.

The poems range over childhood and family, illness and age, marriage and parenthood, love and marital conflict, with biblical and daily-life texts interwoven in the most natural and immediate way. At the outset, in "Nativity," we realize how compatible the Bible stories are with the domain of childhood and the imagination. The poem's structure (a sestina) reflects the interplay of contradictions and opposites, and their many mutations, that will continue throughout the book and that is inherent in the story of Jesus. It begins:

Some parents shy away from the body,

but we hush up about the cross —

rereading our daughter the story about Jesus

we most believe in: mother

and father kneeling after the hard birth,

humbled by the exhaustions of love.

In its alternations and ringing-of-changes on the six repeated words (most of which are different tones of the same, muted vowel), the unstrained sestina suits well the alternations of, and variations on, its ideas. The words Powell commits the poem to — body, cross, Jesus, mother, birth, love — prove up to the task, able to sustain the poem's progression of meaning. This is partly because she lets them assume many forms: As the narrative moves through the six stanzas, "birth" alternates with "death," "Jesus" with "Christ" and "God." "Mother" becomes "Mommy," and also the poet's mother to whom she whispered, "I think God would have picked me as Mother/Mary if he'd sent his son right now", and finally both "Mom" and the "Mary" whose part the child has taken. The cross takes on varied meanings, as an adjective (Herod, jealous and cross), and later, part of the sweet, vivid picture of the poet's baby son, enlisted as Jesus in his sister's play, "a prop, lovingly swaddled in blue dish towels, his head criss-crossed/with paisley scarves…"

In the final two stanzas, the story comes down on the positive side of its dichotomies:

…Suffering and death

keep their distance from the warm house. Jesus

laughs as Mary tickles his brand-new body.

You be the manger, Mom, Mary says. I cross

my legs, sit the baby, fat with love, on the throne of my body,

done with the hard births, the beginnings of God.

At least for now, Jesus need not weep.

"Raising Jesus" is another visit to the domain of childhood, raising the question of "How in the world did Mary do it?" (Powell doesn't waste words — "in the world" is what her question is all about.) Here, in her children's play, fighting, and making up, Peter Pan, pirates and crocodiles blend easily with the story of the baby Jesus, children's murderous impulses with tender, and "the reptilian brain [with] its housemate, the soul." "The story [the children's fight] is solved by a kiss … a real smooch the rapt/Wendy bestows on the born-again Pan," but when the daughter presents her brother ("naked except for the scarf/wrapped twice around his waist and knotted in front") as "Jesus — grown-up!" the mother cannot forget another kiss, and ends with her own prayer:

Oh God, keep me a mediocre Mary!

Dilute my children's love with selfishness,

let them refuse the treacherous kiss, never know

the miserable cup. Make their lives long, happy, ordinary —

and forgive the mother, reaching for Your hem, craving that miracle.

I very much like the passionate mother of these poems. Throughout the book, she pays a wonderful, close attention to her children, making their serious play and literal, preliterate identification with myth visible and real. Her watchful regard is never without an awareness of life's dangers and darkness, but it also has something of Sarah's ironic laughter. The demands of child care do not stop the activity of the poet's imagination, but help it thrive. (We know, of course, that the hard work of giving it form occurs elsewhere and is constantly subject to a mother's myriad interruptions; Powell alludes briefly to this in "Raising Jesus," saying, "Just as I leave the kitchen table and wade/into the day's first pool of quiet,/my daughter appears …") Even if it doesn't settle my friends' argument, the book should be a heartening companion.

Many of the poems are in a structured free verse that establishes a pattern in the first stanza, often five or six lines of five stresses but a varying number of syllables, and then carries it out, giving a sense of order and behind-the-scenes control to the free forms. As in the "Nativity" sestina, Powell is also comfortable with more prescribed structures. In another sestina, "Myth," there's much to reward rereading, with several levels intensifying the impact of the poem. Powell again expands the sestina's fixed repertoire of six words by multiplying forms — past becomes present, future, future, present, past and instead of progression there is symmetry, as the child's imagination takes the Indian legend of Savitri full circle. "This time,/Mom, read the story backwards" suspends time, and "India makes new children/easily, pulling old men and women past/age, youth, the cradle into the midwives' hands."

The first of several sonnets in the book is "After Bonsignori," whose form is well-suited to its Italian backdrop. Powell's note explains that "In Francesco Bonsignori's Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Child, the infant sleeps on the Stone of Unction." (The title of Bonsignori's painting is of course the implied title here as well.) This is a small sonnet for an intimate occasion, its four beats per line similar to Elinor Wylie's tetrameter "Little Sonnet" but its inventive rhymes and spirit are wonderfully contemporary:

He's damp from his bath and mad as hell,

so I nurse him naked as a baby Jesus.

His mouth, quick and expert, eases

my tense breast. Kicks loosen the towel

till it falls aside and reveals the voluptuous

child, boy-orchid and tiny nipples alert.

My hand feels the work of his eager heart.

Now I know what could crush

my life.

The earth moves us into frank noon

while at Castelvecchio the light grows mild.

A sound of heels and the door pulling shut,

Each Mary alone now with her only child.

Warmed just by a meager shirt,

one's already sleeping on a bed of stone.

The last section of the book includes several other sonnets, generally in the more common five-beat line, each a small meditation. "Jupiter" brings together the fact of the physicist-husband's calculation — Jupiter's gravitational pull on the body of a newborn is fifty times stronger than the obstetrician's — with the new mother's less calculated assessment of what unseen forces may exercise their pull on the child once it is outside the shielding womb. "Grace" considers another sort of calculation, an algebra done in the bathroom mirror's "cruel fluorescence" surveying "a negligence/of flesh." The potentially depressing recognition of "what else time aims to write on our tender slate/of skin" leads, in the sestet, to regarding "our fellow grown-/ups now in a different light" and

Grief for those already gone in from the weather

counsels us to prize the quiet damage that the living

must collect — while the sure unknown tethered

to our constants is still a blessed x.

I find myself happily consoled by the idea of "priz(ing) the quiet damage that the living must collect."

It's not surprising to find that the watchful, often adoring mother, so sympathetic to her children's imaginative, biblically-inspired desires, is also the child who created her own vivid, parallel world by taking Bible teaching seriously. "The Calling," "Do This In Remembrance," "Complicities," and the tour de force in the final section, "Rapture," all show what happens when the often nutty injunctions and notions of Biblical text are applied literally. "Rapture" in the final (Job) section, deals with the implications of this promised ascendance of saved souls on the final day. (I assume, since little in Powell is accidental, that although the poem's topic comes from Revelations it is placed in the Job section because it has a kind of existential crisis at its center.)

The child, having taken the Bible Study Group story to heart, and now waiting alone on the sidewalk for her mother to pick her up after a piano lesson, finds herself wondering if the Rapture has taken place without her. This section gives a good indication of Powell's deadpan humor, rooted naturally in the logical consequences of the Biblical teachings:

I dreaded trumpets, quiet as dog whistles,

had called helium souls up, and abandoned me.

I could see our Oldsmobile careening,

driverless, down Dayton Boulevard, the unsaved

drivers strangely blinded to the cars of the elect

flipping upside down in ditches …

There's much more in these poems than children, mother love, memory, and the Bible. "Manna" captures as well as anything I've read the appetites and energy of the first stages of romantic love, with its limitless possibilities, abundant offerings, and inevitable traces of past lovers, seen here through the perspective of the long-married. The premise — cleaning the kitchen, she finds the recipes of her early marriage — by itself makes for a rich metaphor. The ensuing details ring true enough to taste, and poignant:

Nothing was safe in kitchens in the old days

of before-dinner drinks and freesia in the bud vase …

Lime Chiffon with three red stars and a telephone

number inked in beside it — that must be yours,

though it's not your hand that slipped,

Then sprinkle with shivers of chocolate.

Brandied Relish with its little diary in another hand

suggests someone else brought crushed

fresh fruit, whatever is in season routinely

to your ferment:

7/30 wild blues

8/11 red haven peaches

8/24 raspberries and seckel pears …

Because this is Powell, however, there's an added dimension to the metaphor, the poem framed with this opening passage from Numbers:

We remember the fish which we used to eat free in Egypt, the cucumbers and the leeks and the onions and the garlic. But now our soul is dried up. There is nothing at all to look at except this manna.

and this ending:

… how some nights a hunger

still rumbles through our sleep, grips

the belly of our dreams until we wake —

warm as milk within each other's arms,

yet wondering what our Egypts could have lacked.

The two short poems, "In the Garden" and "The Saved," each show that moment when two happily married (to other people) people are drawn to a kiss, which in these poems seems as charged as any sexual union. How could it not be when —

The moon sifts its pale petals

across your shoulders onto my skin, and I want

to whisper as we slowly untouch

the line that faintly floats back: Oh,

the field is white and ready for harvest.

("The Saved")

We see in these poems, and in poems of conjugal love ("Balm," "Vespers," and the book's powerful concluding poem, "Concordance") that passion and sensuous appreciation are not confined to the mother's realm.

There are many more poems that deserve mention for the arresting pictures they paint, their observant juxtaposition of the sacred and domestic, their transparent, playful craft. I recommend any poem where the daughter is involved with crayons (in addition to "Myth," there are "Judgments" and "FORASINADAMALLDIE"); and the funny, vigorous stories about Aunt Roxy ("Witness," "At Ninety-Eight," "Promised Land," "Revelation"). This is a world where the implications of the imagination are taken seriously, and where we're reminded that the Bible is as fertile a source for intelligent, lively contemporary poetry as Homer or Dante. In showing us this world, Powell has created a remarkably unified and satisfying book.

Visit Lynn Powell's Poetry Foundation profile

Visit University of Wisconsin Press' Website

Old & New Testaments

by Lynn Powell

University of Wisconsin Press, 1995

When friends of mine were arguing recently about whether to raise their new baby with or without a conventional religious education, I gave them Lynn Powell's Old & New Testaments (University of Wisconsin Press, 1995). In Powell's hands, the Bible stories and verses, mysteries and perils learned in childhood become a vital myth that colors and deepens almost every aspect of daily life, for both the child and the adult she becomes. One is tempted to conclude that the conditions of a Baptist upbringing are necessary and sufficient to make a poet — that this is the school all poets should go to. Of course, the material is well served by the observant imagination of the child Powell was and the keen intelligence, humor, and sure-footed craft of the adult poet who has clearly found her metier.

Powell's book, winner of the 1995 Brittingham Prize in Poetry, is organized in four parts representing the Old and New Testaments of the title, but not in the expected order: Genesis, Song of Solomon, Revelation, and Job — the beginning, the idyllic time, the end, and finally, returning to the Old Testament's most timeless book, Job, the existential present.

Each part begins with a biblical passage that gives a good indication of what Bible we are talking about and what world we are about to enter. From Genesis:

And he said, I will surely return to you at this time next year;

and behold, Sarah your wife shall have a son.

And Sarah was listening at the tent door …

and Sarah laughed to herself …

From Song of Solomon, there is sensuous desire (for the "garden [that] breathes out fragrance, its spices wafted above", for the beloved to "come into his garden and eat its choice fruits"); from Revelation, the sting of surprise in finding the little book "in my mouth, sweet as honey; but when I had eaten it, my stomach was made bitter;" and from Job, the question:

Where is the way to the dwelling of light?

And darkness, where is its place,

that you may take it to its territory

and that you may discern the paths to its home?

This is a richly physical, natural world full of the apparent opposites of the sweet and bitter, light and dark, as well as laughter.

The poems range over childhood and family, illness and age, marriage and parenthood, love and marital conflict, with biblical and daily-life texts interwoven in the most natural and immediate way. At the outset, in "Nativity," we realize how compatible the Bible stories are with the domain of childhood and the imagination. The poem's structure (a sestina) reflects the interplay of contradictions and opposites, and their many mutations, that will continue throughout the book and that is inherent in the story of Jesus. It begins:

Some parents shy away from the body,

but we hush up about the cross —

rereading our daughter the story about Jesus

we most believe in: mother

and father kneeling after the hard birth,

humbled by the exhaustions of love.

In its alternations and ringing-of-changes on the six repeated words (most of which are different tones of the same, muted vowel), the unstrained sestina suits well the alternations of, and variations on, its ideas. The words Powell commits the poem to — body, cross, Jesus, mother, birth, love — prove up to the task, able to sustain the poem's progression of meaning. This is partly because she lets them assume many forms: As the narrative moves through the six stanzas, "birth" alternates with "death," "Jesus" with "Christ" and "God." "Mother" becomes "Mommy," and also the poet's mother to whom she whispered, "I think God would have picked me as Mother/Mary if he'd sent his son right now", and finally both "Mom" and the "Mary" whose part the child has taken. The cross takes on varied meanings, as an adjective (Herod, jealous and cross), and later, part of the sweet, vivid picture of the poet's baby son, enlisted as Jesus in his sister's play, "a prop, lovingly swaddled in blue dish towels, his head criss-crossed/with paisley scarves…"

In the final two stanzas, the story comes down on the positive side of its dichotomies:

…Suffering and death

keep their distance from the warm house. Jesus

laughs as Mary tickles his brand-new body.

You be the manger, Mom, Mary says. I cross

my legs, sit the baby, fat with love, on the throne of my body,

done with the hard births, the beginnings of God.

At least for now, Jesus need not weep.

"Raising Jesus" is another visit to the domain of childhood, raising the question of "How in the world did Mary do it?" (Powell doesn't waste words — "in the world" is what her question is all about.) Here, in her children's play, fighting, and making up, Peter Pan, pirates and crocodiles blend easily with the story of the baby Jesus, children's murderous impulses with tender, and "the reptilian brain [with] its housemate, the soul." "The story [the children's fight] is solved by a kiss … a real smooch the rapt/Wendy bestows on the born-again Pan," but when the daughter presents her brother ("naked except for the scarf/wrapped twice around his waist and knotted in front") as "Jesus — grown-up!" the mother cannot forget another kiss, and ends with her own prayer:

Oh God, keep me a mediocre Mary!

Dilute my children's love with selfishness,

let them refuse the treacherous kiss, never know

the miserable cup. Make their lives long, happy, ordinary —

and forgive the mother, reaching for Your hem, craving that miracle.

I very much like the passionate mother of these poems. Throughout the book, she pays a wonderful, close attention to her children, making their serious play and literal, preliterate identification with myth visible and real. Her watchful regard is never without an awareness of life's dangers and darkness, but it also has something of Sarah's ironic laughter. The demands of child care do not stop the activity of the poet's imagination, but help it thrive. (We know, of course, that the hard work of giving it form occurs elsewhere and is constantly subject to a mother's myriad interruptions; Powell alludes briefly to this in "Raising Jesus," saying, "Just as I leave the kitchen table and wade/into the day's first pool of quiet,/my daughter appears …") Even if it doesn't settle my friends' argument, the book should be a heartening companion.

Many of the poems are in a structured free verse that establishes a pattern in the first stanza, often five or six lines of five stresses but a varying number of syllables, and then carries it out, giving a sense of order and behind-the-scenes control to the free forms. As in the "Nativity" sestina, Powell is also comfortable with more prescribed structures. In another sestina, "Myth," there's much to reward rereading, with several levels intensifying the impact of the poem. Powell again expands the sestina's fixed repertoire of six words by multiplying forms — past becomes present, future, future, present, past and instead of progression there is symmetry, as the child's imagination takes the Indian legend of Savitri full circle. "This time,/Mom, read the story backwards" suspends time, and "India makes new children/easily, pulling old men and women past/age, youth, the cradle into the midwives' hands."

The first of several sonnets in the book is "After Bonsignori," whose form is well-suited to its Italian backdrop. Powell's note explains that "In Francesco Bonsignori's Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Child, the infant sleeps on the Stone of Unction." (The title of Bonsignori's painting is of course the implied title here as well.) This is a small sonnet for an intimate occasion, its four beats per line similar to Elinor Wylie's tetrameter "Little Sonnet" but its inventive rhymes and spirit are wonderfully contemporary:

He's damp from his bath and mad as hell,

so I nurse him naked as a baby Jesus.

His mouth, quick and expert, eases

my tense breast. Kicks loosen the towel

till it falls aside and reveals the voluptuous

child, boy-orchid and tiny nipples alert.

My hand feels the work of his eager heart.

Now I know what could crush

my life.

The earth moves us into frank noon

while at Castelvecchio the light grows mild.

A sound of heels and the door pulling shut,

Each Mary alone now with her only child.

Warmed just by a meager shirt,

one's already sleeping on a bed of stone.

The last section of the book includes several other sonnets, generally in the more common five-beat line, each a small meditation. "Jupiter" brings together the fact of the physicist-husband's calculation — Jupiter's gravitational pull on the body of a newborn is fifty times stronger than the obstetrician's — with the new mother's less calculated assessment of what unseen forces may exercise their pull on the child once it is outside the shielding womb. "Grace" considers another sort of calculation, an algebra done in the bathroom mirror's "cruel fluorescence" surveying "a negligence/of flesh." The potentially depressing recognition of "what else time aims to write on our tender slate/of skin" leads, in the sestet, to regarding "our fellow grown-/ups now in a different light" and

Grief for those already gone in from the weather

counsels us to prize the quiet damage that the living

must collect — while the sure unknown tethered

to our constants is still a blessed x.

I find myself happily consoled by the idea of "priz(ing) the quiet damage that the living must collect."

It's not surprising to find that the watchful, often adoring mother, so sympathetic to her children's imaginative, biblically-inspired desires, is also the child who created her own vivid, parallel world by taking Bible teaching seriously. "The Calling," "Do This In Remembrance," "Complicities," and the tour de force in the final section, "Rapture," all show what happens when the often nutty injunctions and notions of Biblical text are applied literally. "Rapture" in the final (Job) section, deals with the implications of this promised ascendance of saved souls on the final day. (I assume, since little in Powell is accidental, that although the poem's topic comes from Revelations it is placed in the Job section because it has a kind of existential crisis at its center.)

The child, having taken the Bible Study Group story to heart, and now waiting alone on the sidewalk for her mother to pick her up after a piano lesson, finds herself wondering if the Rapture has taken place without her. This section gives a good indication of Powell's deadpan humor, rooted naturally in the logical consequences of the Biblical teachings:

I dreaded trumpets, quiet as dog whistles,

had called helium souls up, and abandoned me.

I could see our Oldsmobile careening,

driverless, down Dayton Boulevard, the unsaved

drivers strangely blinded to the cars of the elect

flipping upside down in ditches …

There's much more in these poems than children, mother love, memory, and the Bible. "Manna" captures as well as anything I've read the appetites and energy of the first stages of romantic love, with its limitless possibilities, abundant offerings, and inevitable traces of past lovers, seen here through the perspective of the long-married. The premise — cleaning the kitchen, she finds the recipes of her early marriage — by itself makes for a rich metaphor. The ensuing details ring true enough to taste, and poignant:

Nothing was safe in kitchens in the old days

of before-dinner drinks and freesia in the bud vase …

Lime Chiffon with three red stars and a telephone

number inked in beside it — that must be yours,

though it's not your hand that slipped,

Then sprinkle with shivers of chocolate.

Brandied Relish with its little diary in another hand

suggests someone else brought crushed

fresh fruit, whatever is in season routinely

to your ferment:

7/30 wild blues

8/11 red haven peaches

8/24 raspberries and seckel pears …

Because this is Powell, however, there's an added dimension to the metaphor, the poem framed with this opening passage from Numbers:

We remember the fish which we used to eat free in Egypt, the cucumbers and the leeks and the onions and the garlic. But now our soul is dried up. There is nothing at all to look at except this manna.

and this ending:

… how some nights a hunger

still rumbles through our sleep, grips

the belly of our dreams until we wake —

warm as milk within each other's arms,

yet wondering what our Egypts could have lacked.

The two short poems, "In the Garden" and "The Saved," each show that moment when two happily married (to other people) people are drawn to a kiss, which in these poems seems as charged as any sexual union. How could it not be when —

The moon sifts its pale petals

across your shoulders onto my skin, and I want

to whisper as we slowly untouch

the line that faintly floats back: Oh,

the field is white and ready for harvest.

("The Saved")

We see in these poems, and in poems of conjugal love ("Balm," "Vespers," and the book's powerful concluding poem, "Concordance") that passion and sensuous appreciation are not confined to the mother's realm.

There are many more poems that deserve mention for the arresting pictures they paint, their observant juxtaposition of the sacred and domestic, their transparent, playful craft. I recommend any poem where the daughter is involved with crayons (in addition to "Myth," there are "Judgments" and "FORASINADAMALLDIE"); and the funny, vigorous stories about Aunt Roxy ("Witness," "At Ninety-Eight," "Promised Land," "Revelation"). This is a world where the implications of the imagination are taken seriously, and where we're reminded that the Bible is as fertile a source for intelligent, lively contemporary poetry as Homer or Dante. In showing us this world, Powell has created a remarkably unified and satisfying book.

Visit Lynn Powell's Poetry Foundation profile

Visit University of Wisconsin Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.