ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Levi Todd is a poet and witness to the Chicago Renaissance. He currently serves as Founder and Executive Director of Reacting Out Loud, an organization devoted to uplifting poetry and affirming community in Muncie, IN. He is also a reader for Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and has work published or forthcoming in The Indianola Review, thread arts collective, and workshop anthologies from Blueshift Journal and Winter Tangerine.

March 21, 2017

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

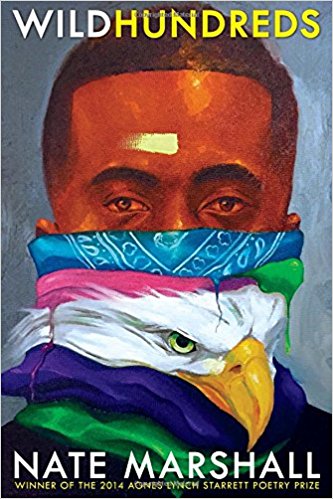

Review of Wild Hundreds by Nate Marshall

Wild Hundreds

by Nate Marshall

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015

I first encountered Nate Marshall when my high school creative writing teacher showed us the documentary Louder Than A Bomb, which focused on the Chicago youth poetry slam (of the same name) and its influence. Afterwards, I watched videos of him performing "Look" and "LeBron James" on repeat, hooked on his seemingly effortless rhythm and energy. The Nate Marshall I knew from those videos was full of confidence, but always made time for a more emotional appeal waiting underneath subtle machismo. Since his high school years, he has gone on to join the Dark Noise poetry collective, become a co-editor of The Breakbeat Poets, and won a Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship, among many other awards. The Nate Marshall presented in Wild Hundreds (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015) is conscious, brutally honest, and puts on no front to hide the emotion in each poem.

"Wild Hundreds" is the nickname given to the predominantly Black southside neighborhood of Chicago, which many outsiders reduce to a monolith of crime, drug use, and violence. A native Chicagoan, Marshall provides an empathetic narrative of his community that is summarized well by his preface to the third part of the collection. He uses a Nelson Algren quote from the essay "Chicago: City on the Make" that states, "once you've come to be part of this particular patch, you'll never love another. Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real." Marshall's embrace of the Hundreds and its wildness is full of grim understanding, and shines a light on a neighborhood that is so often cast off as irreparable.

Marshall includes six short poems scattered throughout the collection entitled "Chicago high school love letters" that provide a kind of backbone to the other pieces. Each one is given a date, such as "first day of school", "homecoming weekend", "prom night", etc. Each piece is one to two stanzas long, and introduced with a number ranging from 1 in the first poem to 333 in the last one. Each delivers powerful confessions to an unnamed lover, such as:

i would fight for you

like my shoes or my

boys or any excuse

for contact.

It is only until the last poem, which reads,

graduation

333.

hold me

before

i

disappear

that a footnote explains that the numbers represent the number of homicides in Chicago throughout the 2007-2008 school year. This theme of navigating violence in the Wild Hundreds while trying to love and survive despite the feeling of inevitability is prevalent throughout the collection.

Marshall also demonstrates an incredible control of form in several poems while making it seem almost effortless and far from a gimmick. The occasional form used in Wild Hundreds comes across as fitting and almost necessary for the content it presents. In "Ragtown prayer," Marshall includes a Facebook post from a friend written after the murder of Tyrone Lawson, and rewrites it by rearranging and slightly altering the words in each line. For example, he takes "Dear Heavenly Father/As we gather 2ma [tomorrow] wit broken/hearts, lost souls, & heavy/emotions to bury our love" and changes it to:

No Father (Maybe He Heavenly?).

2ma is broken. what we gather

from this heavy life is souls, hearts

buried emotions, our love.

By reconstructing the Facebook post, Marshall visually recreates how loss can reshape one's interpretation of the world around them. His ability to make rigid structure seem natural and fluid is evident as he goes on to include sestinas and reverse poems in which the reader doesn't recognize form at first glance.

Nate Marshall's portrait of his community is difficult to describe in the fact that it is presented with both fearful awe and the heartfelt admiration that one feels for home. Wild Hundreds is the story of a community trying to connect, love, and create despite everything that suggests a different fate for the infamous neighborhood. This awareness is reflected well in the poem "learning gang handshakes" in which Marshall writes,

when the big boys taught me how to hug with palms

i learned the secret. shaking up looks like violence

& love. & it is.

What is most striking in this collection is his acute awareness of why the Wild Hundreds have such a crooked history of crime and violence, as he explores how racism, poverty, and redlining have influenced the neighborhood and Chicago as a whole. But beyond this understanding, Marshall imparts a sense of urgency on the reader. In "out south" he explains,

in Chicago kids are beaten. they crack

open; they're pavement. they don't fight, they die.

[…]

every kid that's killed is one less free lunch,

a fiscal coup. welcome to where we from.

Wild Hundreds isn't conveniently filled with hope that leaves the reader feeling satisfied; this is no Carl Sandburg's "Chicago." Nate Marshall's collection truly is a "long love song" to the Hundreds — but there is just as much funeral dirge beneath it.

Visit Nate Marshall's Website

Visit University of Pittsburgh Press' Website

Wild Hundreds

by Nate Marshall

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015

I first encountered Nate Marshall when my high school creative writing teacher showed us the documentary Louder Than A Bomb, which focused on the Chicago youth poetry slam (of the same name) and its influence. Afterwards, I watched videos of him performing "Look" and "LeBron James" on repeat, hooked on his seemingly effortless rhythm and energy. The Nate Marshall I knew from those videos was full of confidence, but always made time for a more emotional appeal waiting underneath subtle machismo. Since his high school years, he has gone on to join the Dark Noise poetry collective, become a co-editor of The Breakbeat Poets, and won a Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship, among many other awards. The Nate Marshall presented in Wild Hundreds (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015) is conscious, brutally honest, and puts on no front to hide the emotion in each poem.

"Wild Hundreds" is the nickname given to the predominantly Black southside neighborhood of Chicago, which many outsiders reduce to a monolith of crime, drug use, and violence. A native Chicagoan, Marshall provides an empathetic narrative of his community that is summarized well by his preface to the third part of the collection. He uses a Nelson Algren quote from the essay "Chicago: City on the Make" that states, "once you've come to be part of this particular patch, you'll never love another. Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real." Marshall's embrace of the Hundreds and its wildness is full of grim understanding, and shines a light on a neighborhood that is so often cast off as irreparable.

Marshall includes six short poems scattered throughout the collection entitled "Chicago high school love letters" that provide a kind of backbone to the other pieces. Each one is given a date, such as "first day of school", "homecoming weekend", "prom night", etc. Each piece is one to two stanzas long, and introduced with a number ranging from 1 in the first poem to 333 in the last one. Each delivers powerful confessions to an unnamed lover, such as:

i would fight for you

like my shoes or my

boys or any excuse

for contact.

It is only until the last poem, which reads,

graduation

333.

hold me

before

i

disappear

that a footnote explains that the numbers represent the number of homicides in Chicago throughout the 2007-2008 school year. This theme of navigating violence in the Wild Hundreds while trying to love and survive despite the feeling of inevitability is prevalent throughout the collection.

Marshall also demonstrates an incredible control of form in several poems while making it seem almost effortless and far from a gimmick. The occasional form used in Wild Hundreds comes across as fitting and almost necessary for the content it presents. In "Ragtown prayer," Marshall includes a Facebook post from a friend written after the murder of Tyrone Lawson, and rewrites it by rearranging and slightly altering the words in each line. For example, he takes "Dear Heavenly Father/As we gather 2ma [tomorrow] wit broken/hearts, lost souls, & heavy/emotions to bury our love" and changes it to:

No Father (Maybe He Heavenly?).

2ma is broken. what we gather

from this heavy life is souls, hearts

buried emotions, our love.

By reconstructing the Facebook post, Marshall visually recreates how loss can reshape one's interpretation of the world around them. His ability to make rigid structure seem natural and fluid is evident as he goes on to include sestinas and reverse poems in which the reader doesn't recognize form at first glance.

Nate Marshall's portrait of his community is difficult to describe in the fact that it is presented with both fearful awe and the heartfelt admiration that one feels for home. Wild Hundreds is the story of a community trying to connect, love, and create despite everything that suggests a different fate for the infamous neighborhood. This awareness is reflected well in the poem "learning gang handshakes" in which Marshall writes,

when the big boys taught me how to hug with palms

i learned the secret. shaking up looks like violence

& love. & it is.

What is most striking in this collection is his acute awareness of why the Wild Hundreds have such a crooked history of crime and violence, as he explores how racism, poverty, and redlining have influenced the neighborhood and Chicago as a whole. But beyond this understanding, Marshall imparts a sense of urgency on the reader. In "out south" he explains,

in Chicago kids are beaten. they crack

open; they're pavement. they don't fight, they die.

[…]

every kid that's killed is one less free lunch,

a fiscal coup. welcome to where we from.

Wild Hundreds isn't conveniently filled with hope that leaves the reader feeling satisfied; this is no Carl Sandburg's "Chicago." Nate Marshall's collection truly is a "long love song" to the Hundreds — but there is just as much funeral dirge beneath it.

Visit Nate Marshall's Website

Visit University of Pittsburgh Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.