ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Cody Stetzel is a PNW resident working within electrical engineering. He has worked as the managing editor for Five:2:One Magazine and is currently a staff book reviewer for Glass Poetry Press. He received his Masters in Creative Writing for Poetry from the University of California at Davis. His writing can be found previously in the Birmingham Arts Journal, Across the Margins, Boston Accent Literature, Aster(ix) Journal, Glass Poetry Press, and more. Find him on twitter or at his website.

April 13, 2022

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

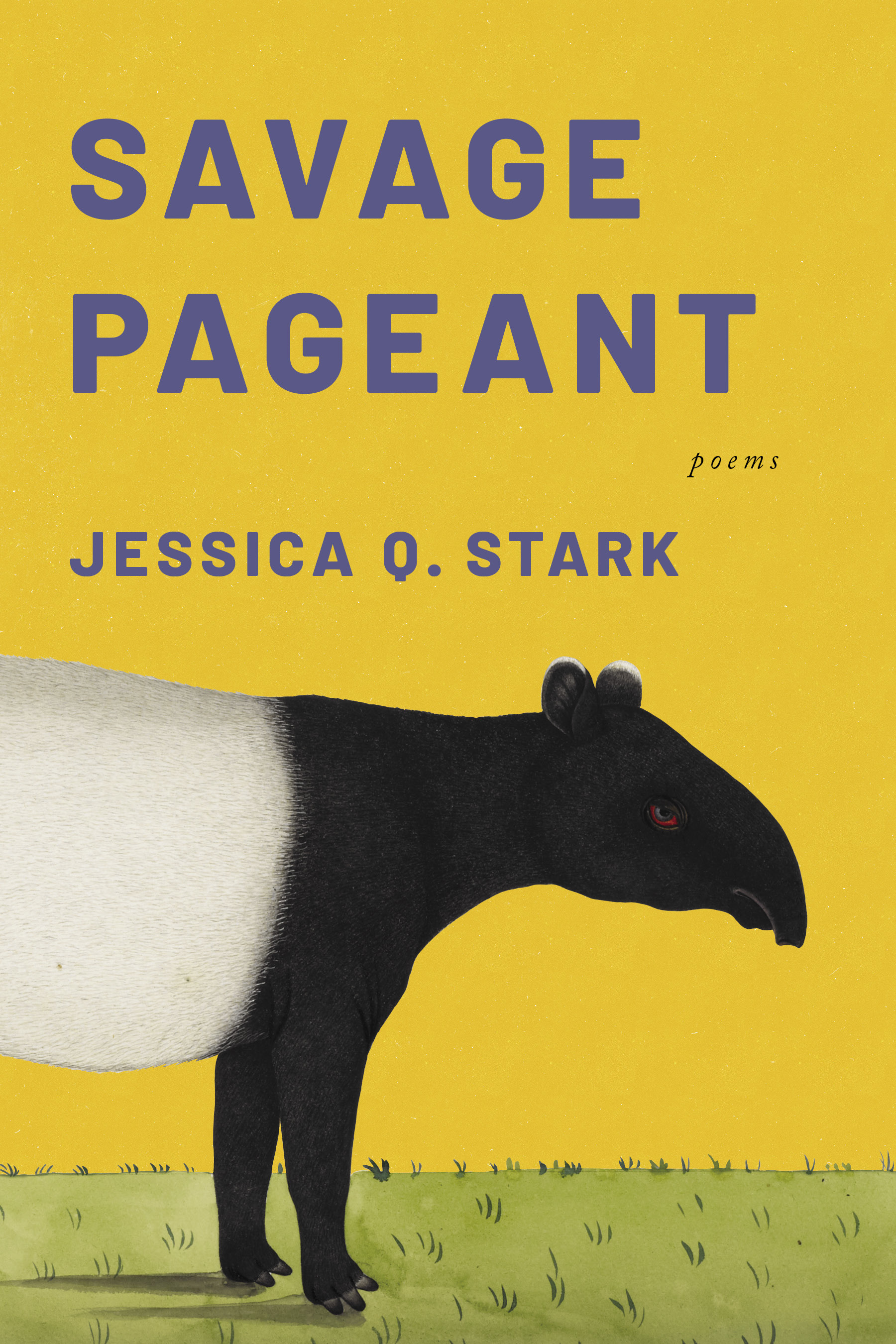

How to Sell 1800 Animals at Auction: A Review of Savage Pageant by Jessica Q. Stark

Savage Pageant

by Jessica Q. Stark

Birds LLC Press, 2020

I’ve learned, after minute research, that there are over 40 million boxes of animal crackers sold around the world each year, still. After 116 years of producing animal crackers, Barnum (but mostly the parent company Nabisco) introduced a new box design to free the animals from their cages. If there are 22 animal crackers and 37 variants per box, there are 880 million animals freed each year now. The arithmetic of the image of freedom. Alternatively, Zoos have been seen throughout history but the first of which arrived in the U.S. in 1874 for Philadelphia. And, further back yet, 1833 is considered the introductory year to the wild animals in circuses with one Isaac A. Van Amburgh jumping into a cage with big cats.

Fortunately, we are not here for the full history of zoos or circuses. Instead, we are here having been given the history of one Jungleland. One Jungleland, several lives intertwined, a few big cats, a few elephants, and the question of: what is the uniting story behind this tumultuous history of Jungleland, its property, the value of its property and its creatures, the development of an area, the growth of a people, and the damages accrued along the way?

When first reading through Jessica Q. Stark’s Savage Pageant (Birds LLC Press , 2020), I felt as though I’d forgotten what it was I was reading. So gripped by the need to know more about the rise and fall of Jungleland and its performers, I felt myself immersed in a tragic play of some kind, sitting alone in an audience looking down at a decrepit stage gives footing to some tenacious dramatists. I pictured the lives of these performers - aging themselves before crumbling into a form of dust, blowing away. Stark writes in 'The End of An Auction',

Savage Pageant

by Jessica Q. Stark

Birds LLC Press, 2020

I’ve learned, after minute research, that there are over 40 million boxes of animal crackers sold around the world each year, still. After 116 years of producing animal crackers, Barnum (but mostly the parent company Nabisco) introduced a new box design to free the animals from their cages. If there are 22 animal crackers and 37 variants per box, there are 880 million animals freed each year now. The arithmetic of the image of freedom. Alternatively, Zoos have been seen throughout history but the first of which arrived in the U.S. in 1874 for Philadelphia. And, further back yet, 1833 is considered the introductory year to the wild animals in circuses with one Isaac A. Van Amburgh jumping into a cage with big cats.

Fortunately, we are not here for the full history of zoos or circuses. Instead, we are here having been given the history of one Jungleland. One Jungleland, several lives intertwined, a few big cats, a few elephants, and the question of: what is the uniting story behind this tumultuous history of Jungleland, its property, the value of its property and its creatures, the development of an area, the growth of a people, and the damages accrued along the way?

When first reading through Jessica Q. Stark’s Savage Pageant (Birds LLC Press , 2020), I felt as though I’d forgotten what it was I was reading. So gripped by the need to know more about the rise and fall of Jungleland and its performers, I felt myself immersed in a tragic play of some kind, sitting alone in an audience looking down at a decrepit stage gives footing to some tenacious dramatists. I pictured the lives of these performers - aging themselves before crumbling into a form of dust, blowing away. Stark writes in 'The End of An Auction',We are on short duration

with these distractions.

Everything is electric in

finitude.

a form of ars poetica, I’d argue. The distractions from daily life and the grandiosity of it all, a circus, a performance, generates this electricity. Energy, in this instance, is what I believe the book is about: the necessary manifestations to get one through their hours.

The exercise of reading Savage Pageant was one in questioning and investigation. My questions through the pages were why is so much strife tied to this particular property? Are all locations like this - lined with these traumas? And if that’s the case, to whose obligation are we working in detailing these archives? Stark wrote, “I am not trying to fashion / photographs out of ghosts” in her poem 'Mass Psychogenic Illness'. A reminder that the poems in this book are more than still frames, they are living monuments asking questions themselves, desiring and interacting with the reader as much as we are with them. The connection to Oedipus and the Sphinx, her tragic death from his unraveling of her riddles, is tangible to me, and reminds me of Wilfred Bion’s writing in 'Elements of Psycho-analysis', “The Sphinx stimulates curiosity and threatens death as the penalty for failure to satisfy it. It can represent the function Freud attributed to attention, but it implies a threat against the curiosity it stimulates.” So much of archive and tragedy revolves around the question, and I think what Stark works with the most is, a question is leading to an answer and what is that leading (or leading away) from?

Therein temporality becomes a living, dynamic structure, affixed with the faces of those who have struggled and strove within it. Savage Pageant paints these portraitures as they are struggling, in the intermittent moments when they are laughing, and in the common dealings in-between. The place of Jungleland though, whether it were bars, cages, and individuals with snacks or a simple property occupied due to the result of new city zoning mechanisms and infrastructure architected, remains dutifully tied with associations to these memories, these faces. Dylan Trigg, in his work The Memory of Place, writes,

The neutralization of the past, experienced when memory’s death throe reaches its end, is productive: It produces nothing less than a temporal mirror. Referred to as the “end of memory,” this flattening-out of the past spits back scatterings of old selves: I have come to haunt myself, and I do this through recognizing the damaged space where the desire of the present once existed.

I think Stark understands this, “I have come to haunt myself,” sentiment well - as Jungleland seems to have come to haunt itself, not only itself as iconic entertainment hub but also itself as mirrored representation of restricted freedom for the wiles of others, as mirrored representation of procedural trauma. After all, as Stark writes in 'A Note for Mabel, Mabel, Tiger Trainer', “The root of entertainment / is the ruse of control.”

The more Stark’s work continues, the more surreal, unreal, or associative it becomes. Its groundedness in Jungleland’s genealogies themselves even becomes jeopardized as they take on the ‘scattering of old selves.’ A mirror shattered begins to look like a funhouse mirror shattered, retaining its reality-altering effects, making the reader question whose traumas and whose faces we are really looking at buried between and underneath the lines. In 'Jungleland Geneaology: 1956 – 1969' Stark writes, “In the intimate harmony of walls and furniture, it may be said that we become conscious of a house that is built by women from the inside, since men only know how to build a house from the outside, and they know little or nothing about “wax” civilization.” And I think in this intimate harmony it may also be said that we become conscious of a falling house from the inside, since the outside structures are the last to lose their integrity.

So what is at stake in witnessing this history of Jungleland, lineated by the characters that struggled to ensure its (and their) survival. I would suppose it is a witnessing of evocative pain that gets erased as a city moves past its allowed existence - the gradual overtaking of a river rock by its moss. “You carried not a single piece, not a photograph, nothing to evoke your memory, abandoned all to see your nation freed,” writes Therese Hak Kyung Cha in Dictee, and gives, in my opinion, a summarizing view of Stark’s relationships with the citizens of Jungleland: they had abandoned everything to live in their Jungleland free, and even then, Jungleland was unfreed. The poems in Savage Pageant are not met with a cynicism, not met with a despondency, but instead seem to be met with a form of remorse. That if only these individuals knew what was in store for Jungleland due to the shifting landscape of Ventura county, they might have lived differently. Or, if Ventura county could have imagined itself with a maintained relationship with Jungleland, what differences would have been made. In 'Savage Pageant: 33 Weeks', “And even if you can’t // jump ship, you might not / need to find your way home.”

Visit Jessica Q. Stark's Website

Visit Birds LLC Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.