ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Cody Stetzel received his MA in Creative Writing in poetry from the University of California at Davis. While from Rochester, New York, the former upstate & northeast hermit has replaced his slow-moving winter energies with the vitality of the west coast. His work has appeared in The East Coast Literary Review and Neovox: International.

March 6, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

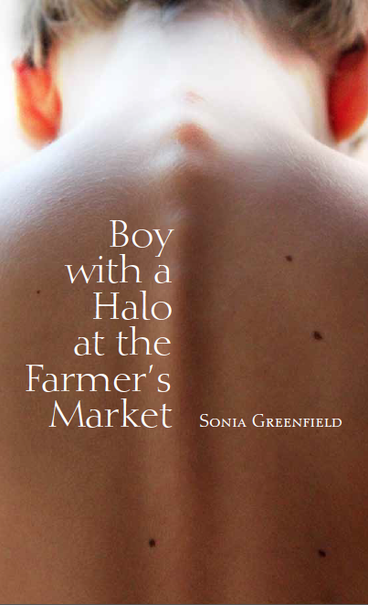

You People Have Eaten Me: Review of Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market by Sonia Greenfield

Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market

by Sonia Greenfield

Codhill Press, 2015

We walk through the farmer's market to browse the stands and smell. In California, it is warm grease of hot dogs and tacos. In New York, it is post-rain and caramel corn. In Washington, it is bread and fish. We walk through the farmer's market and note the collections: the farm-stands, the wineries and the honey-stands, the craft sellers, the celebrators playing music. These are our elements, this is how we split.

Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market by Sonia Greenfield (Codhill Press, 2015)denotes the split of elements in her poem, "The Lost Boys": "It is always telegraphed / when boys are fed / to the elements." While she doesn't go so far as to split the farmer's market she's writing in directly, I find that her poems reconcile with the respective territories of the individual farmer's market elements.

One of the stands Greenfield is looking at, walking past, and working through in her understanding, is pointing at the spectrum of male malevolence. I think of this excerpt from, "Roadside, Railside Diner":

and Pop it was maybe good

that you went when you did

cause the diner folded soon after

and the people you trusted

all went a little wrong.

The farm stands with their abundant fruits and veggies bring in the observant, critical maternal watching the raised men; at once full of care, and, from the inflicted violences of history, maintaining enough distance to be wary.

The sweet and imbibing temptations of wine, honey, vinegars, and other augments are the self-critical maternal modes — they do not read as guilt, but these pieces are conscious and aware in their attempt to contextualize the interstices of violence that have been internalized. In her poem, "Rock Tumbler," Greenfield writes: "and it was the year / the boys kissed the girls while I learned / to vanish or get beat," in a stunning poem regarding the idea of presentation within the body tragic and without. The internal lessons that her poems talk about often move with and around men terrible with their uncaringness. These men, and in turn her poems, are abundant though, like the rows upon rows of potatoes and kale, nuanced only by the personality that is selling them.

The craft sellers and artisan-appearing stands are her pieces more directly speaking toward art, what it means to be writing in this world where one's influence in any given month is a flip of a coin. And like with anything, how if you put enough of your heart into it then, of course, it is most likely to harm you — like this excerpt from "I Shouldn't Even Write This":

and when you nearly died

for your next line

like a poem

aches toward the white

at the end of a page

those metaphors were not mine

This poem in particular, "I Shouldn't Even Write This," is a feeling that I struggle with so often — understanding the weight behind someone's words, feeling it resonate in me — but also being fully aware of how these words are not mine. It isn't a shame, guilt, or pride; like an intuitive form of knowledge, that if my mouth was the one speaking these words I would be betraying the power of my own language.

Oh, and the celebrations — the solo trumpeteers, the viola players, the singers and dancers — these are the poems Greenfield chooses to punch toward the political landscape: whose expressions are highlighted despite the coinflip? "A Spokesperson Said Thoughts and Prayers Go Out" begins with:

Out like what? Whispers

in a tin can tied with yarn

a thousand miles long

to the can of a woman, her

ear desperately pressed

to its emptiness?

Conveying not the easy anger with which one can feel toward the helplessness of those 'thoughts and prayers' statements, but an engagement, a tempting of the world to try and cut through the fog surrounding the need for such sentiments.

In September, I drove to Toronto from Rochester, New York to pick-up my sister from the airport there. I did not plan properly and lost my map-directions as soon as I got into Canada. I showed up at the airport an hour late, and my sister was still finagling her way through international security after having frequented a half-dozen eastern European countries. On our way back, we stopped at a Chipotle in a mall that physically disgusted me with its bougieness. Then, as we passed back into the U.S., despite having no stoppage going into Canada, we were forced to stop from border police and have our car get x-rayed. The moral of this memory is that I am disturbed by comfort. So, when I say I love a farmer's market I do so with the sinking feeling that the presence of comfort, should it rear its head, will quake me.

I go to a farmer's market near my rental every other weekend to get a loaf of bread and stock-up on veggies that will last inordinately long. I've become a person who, when the café I frequent has an above-average amount of business, or a stand I like has a line, there's a certain joy in knowing that they've gained business and they might continue for a short while longer. This joy is extremely conflicting to me; on one hand, the people behind the stands and counters I know nothing about, they could be uncaring humans; on the other hand, in their providing for me, they tend to be very nice individuals. I've found this is one of the most reliable metrics for my returning to any particular business: if I witness someone's kindness there. Greenfield's collection captures this conflict in words that are more apt than I could ever hope to vocalize: the desire for observable kindness, the knowledge that any body is capable of violence in their private domains.

The organization of this collection feels like the violent structuring of a farmer's market to me — its neat separation of necessities, gifts, conveniences, and aesthetics. It profoundly speaks to the nuances of gendered behaviors and seems to sing about the one goal behind any criticism or observation; that, like a detective, Greenfield is looking for the driving, hard, and loving compassion. I hope you consider delving into the beautiful and charming observations that Greenfield lays out on these pages.

Visit Sonia Greenfield's Website

Visit Codhill Press' Website

Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market

by Sonia Greenfield

Codhill Press, 2015

We walk through the farmer's market to browse the stands and smell. In California, it is warm grease of hot dogs and tacos. In New York, it is post-rain and caramel corn. In Washington, it is bread and fish. We walk through the farmer's market and note the collections: the farm-stands, the wineries and the honey-stands, the craft sellers, the celebrators playing music. These are our elements, this is how we split.

Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market by Sonia Greenfield (Codhill Press, 2015)denotes the split of elements in her poem, "The Lost Boys": "It is always telegraphed / when boys are fed / to the elements." While she doesn't go so far as to split the farmer's market she's writing in directly, I find that her poems reconcile with the respective territories of the individual farmer's market elements.

One of the stands Greenfield is looking at, walking past, and working through in her understanding, is pointing at the spectrum of male malevolence. I think of this excerpt from, "Roadside, Railside Diner":

and Pop it was maybe good

that you went when you did

cause the diner folded soon after

and the people you trusted

all went a little wrong.

The farm stands with their abundant fruits and veggies bring in the observant, critical maternal watching the raised men; at once full of care, and, from the inflicted violences of history, maintaining enough distance to be wary.

The sweet and imbibing temptations of wine, honey, vinegars, and other augments are the self-critical maternal modes — they do not read as guilt, but these pieces are conscious and aware in their attempt to contextualize the interstices of violence that have been internalized. In her poem, "Rock Tumbler," Greenfield writes: "and it was the year / the boys kissed the girls while I learned / to vanish or get beat," in a stunning poem regarding the idea of presentation within the body tragic and without. The internal lessons that her poems talk about often move with and around men terrible with their uncaringness. These men, and in turn her poems, are abundant though, like the rows upon rows of potatoes and kale, nuanced only by the personality that is selling them.

The craft sellers and artisan-appearing stands are her pieces more directly speaking toward art, what it means to be writing in this world where one's influence in any given month is a flip of a coin. And like with anything, how if you put enough of your heart into it then, of course, it is most likely to harm you — like this excerpt from "I Shouldn't Even Write This":

and when you nearly died

for your next line

like a poem

aches toward the white

at the end of a page

those metaphors were not mine

This poem in particular, "I Shouldn't Even Write This," is a feeling that I struggle with so often — understanding the weight behind someone's words, feeling it resonate in me — but also being fully aware of how these words are not mine. It isn't a shame, guilt, or pride; like an intuitive form of knowledge, that if my mouth was the one speaking these words I would be betraying the power of my own language.

Oh, and the celebrations — the solo trumpeteers, the viola players, the singers and dancers — these are the poems Greenfield chooses to punch toward the political landscape: whose expressions are highlighted despite the coinflip? "A Spokesperson Said Thoughts and Prayers Go Out" begins with:

Out like what? Whispers

in a tin can tied with yarn

a thousand miles long

to the can of a woman, her

ear desperately pressed

to its emptiness?

Conveying not the easy anger with which one can feel toward the helplessness of those 'thoughts and prayers' statements, but an engagement, a tempting of the world to try and cut through the fog surrounding the need for such sentiments.

In September, I drove to Toronto from Rochester, New York to pick-up my sister from the airport there. I did not plan properly and lost my map-directions as soon as I got into Canada. I showed up at the airport an hour late, and my sister was still finagling her way through international security after having frequented a half-dozen eastern European countries. On our way back, we stopped at a Chipotle in a mall that physically disgusted me with its bougieness. Then, as we passed back into the U.S., despite having no stoppage going into Canada, we were forced to stop from border police and have our car get x-rayed. The moral of this memory is that I am disturbed by comfort. So, when I say I love a farmer's market I do so with the sinking feeling that the presence of comfort, should it rear its head, will quake me.

I go to a farmer's market near my rental every other weekend to get a loaf of bread and stock-up on veggies that will last inordinately long. I've become a person who, when the café I frequent has an above-average amount of business, or a stand I like has a line, there's a certain joy in knowing that they've gained business and they might continue for a short while longer. This joy is extremely conflicting to me; on one hand, the people behind the stands and counters I know nothing about, they could be uncaring humans; on the other hand, in their providing for me, they tend to be very nice individuals. I've found this is one of the most reliable metrics for my returning to any particular business: if I witness someone's kindness there. Greenfield's collection captures this conflict in words that are more apt than I could ever hope to vocalize: the desire for observable kindness, the knowledge that any body is capable of violence in their private domains.

The organization of this collection feels like the violent structuring of a farmer's market to me — its neat separation of necessities, gifts, conveniences, and aesthetics. It profoundly speaks to the nuances of gendered behaviors and seems to sing about the one goal behind any criticism or observation; that, like a detective, Greenfield is looking for the driving, hard, and loving compassion. I hope you consider delving into the beautiful and charming observations that Greenfield lays out on these pages.

Visit Sonia Greenfield's Website

Visit Codhill Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.