ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Cody Stetzel received his MA in Creative Writing in poetry from the University of California at Davis. While from Rochester, New York, the former upstate & northeast hermit has replaced his slow-moving winter energies with the vitality of the west coast. His work has appeared in The East Coast Literary Review and Neovox: International.

July 5, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Her Mother Called Her Angel: Review of Smile! by Denise Duhamel

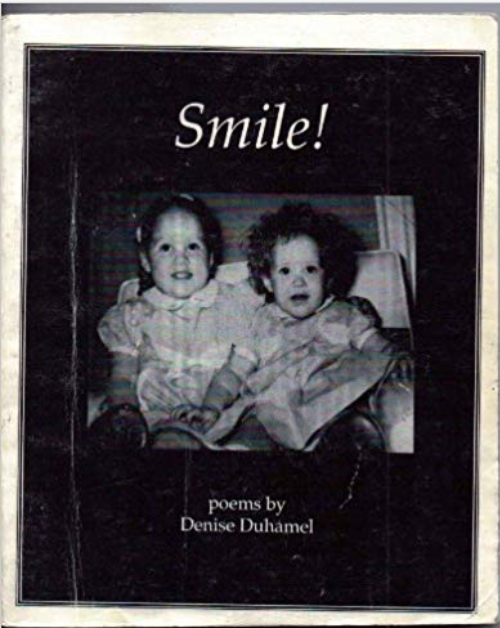

Smile!

by Denise Duhamel

Warm Spring Press, 1993

I had a very informative conversation with a mentor of mine whom, upon reading part of my thesis manuscript, asked me to revise it to step away from my sweeping, generalizing statements. You know the type, ‘All x is y,’ or ‘[Insert large concept] is [reduction]’ — oh I was so awful! So violent with my metaphors to dwindle everything into a more manageable variation. This is to preface my next statement with my self-awareness: I am going to make a sweeping statement, and I know, I know. Ugh.

Poetry’s success, for me, largely resides in speaking both to unspeakability and placing the reader beyond this unspeakability. I make this statement because Denise Duhamel’s Smile! makes this process feel so tangible to me.

In Smile!, Duhamel writes a book of poems in a trio of sections wherein the first two read more historically rooted through gender and references to location, and the final section, “Smile!”, turns into the expansion beyond reference; moving toward unspeakability, and then placing beyond. This book approaches the stories of grief & abuse & yearning to resolve one’s loneliness. From the continual reminders of lovers and friends being afflicted or falling to AIDS to the omnipresence of masculinity, that bulky weakness, which stalks her speakers & presses into any domain of authority within their lives.

Many approaches to these concepts — trauma, grief — feel very vulnerable and inquisitive in the writer and speaker’s attempts for understanding. What surprises me with Duhamel, though, is on first reading I did not think this book was very questioning — except for the following Boy George poem, none of the pieces seemed to really be searching for something — the trauma already seems understood. I went back and counted 32 questions through these 97 pages of poems. I don’t think my lack of observation in these poems was inattentiveness, but rather that the poems never seem to rely on a question to point toward unspeakability. This poem seems to write so specifically on unknowing or knowing or projecting or relating, “On Being Born the Same Exact Day of the Same Exact Year as Boy George”:

In the latest articles, Boy George is claiming he’s not

really happy. Hmm, I think, just like me.

when he comes to New York and stays at hotels in Gramercy Park

Maybe he feels a pull to the Lower East Side,

wanders towards places where I am, but not knowing me, doesn’t know why.

This book feels very in-the-head, psychoanalytic. Elizabeth Grosz, in her work Jacques Lacan: A Feminist Introduction, parses through a concoction of Freud, Kristeva, Lacan, Irigaray and other psychoanalysts to enable, what I find, to be a strong interpretation as well as digestible discussion on psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic impact on femininity and feminism. Grosz writes:

In short, the symbolic/oedipal/social mode owes a debt of existence to an unspeakable and unrepresentable semiotic/maternal/feminine. The symbolic cannot even acknowledge, let alone repay, the debt that the oedipal and the conscious owe to the pre-oedipal and the unconscious. This debt is the social equivalent of the debt the subject owes to a female corporeality which remains unrecognized in its autonomy.

I like to think about this moment, the symbolic debt to the feminine, with respect to another of Duhamel’s poems in this book. In “Kitchen,” she begins the poem,

I’m jealous when my mother touches anything else.

the potatoes that roll in the stainless steel sink.

the water runs and my mother rubs each bump —

under their chins, behind their necks — clean.

Sometimes she bathes me here, washes my hair

kneading small circles on my scalp. I trust her,

On one hand, readers are entering this poem through a very real moment of preparation, which feels like a central poetics for this book. On the other hand, the poems in Smile! are ripe with female figures and characters — coworkers, family members, friends, loves — who are all being documented with a similar stoicism towards traumas and abuses. The poetics of preparation is speaking towards how a female individual is equipped to handle the surrounding, future pain of their associates.

The final section feels more personal than the first two — she starts off with an experience of rape from a dentist. This section, and this book, sticks with me. Both took me some time to work through. I would go depressed reading it; not quite depressed in the sense that I’m blaming the book but more depressed in the sense of utter melancholy. Then there are poems which made me laugh through their cynicism? I add a question mark because I don’t think they’re truly cynical but I don’t have much of a better word to describe them. It’s cynical in the way that a self-deprecating joke is. Like a job interview where upon being asked what your strengths are you firmly answer No strengths, but people like to talk to me about their problems. I think of Duhamel’s poem, “Sometimes the First Boys Don’t Count”:

She was holding a wrench

to her lips. Your dad looked at me the same way you did,

but that was how I wanted to be looked at then--that was how

I thought it should be. You washed the grease from your hands,

wiped your brow with your forearm and were ready.

It is full of the trauma that many of her poems hold close, and yet through the pain I still find myself laughing at the familiar ineptitude of men, their griminess that if I sit with for too long disturbs me.

The reason why I bring up the psychoanalytic function of this book is because I read the following quote and immediately felt as though Duhamel and Grosz were directly in conversation here:

In so far as she is mother, woman remains unable to speak her femininity or her maternity. She remains locked within a mute, rhythmic, spasmic, potentially hysterical - and thus speechless body, unable to accede to the symbolic because 'she' is too closely identified with/ as the semiotic. 'She' is the unspeakable condition of the child's speech.

Duhamel seems to be actively fighting that unspeakable condition, while actively embodying that rhythmic, spasmic, and potentially hysterical mode.

Smile!

by Denise Duhamel

Warm Spring Press, 1993

I had a very informative conversation with a mentor of mine whom, upon reading part of my thesis manuscript, asked me to revise it to step away from my sweeping, generalizing statements. You know the type, ‘All x is y,’ or ‘[Insert large concept] is [reduction]’ — oh I was so awful! So violent with my metaphors to dwindle everything into a more manageable variation. This is to preface my next statement with my self-awareness: I am going to make a sweeping statement, and I know, I know. Ugh.

Poetry’s success, for me, largely resides in speaking both to unspeakability and placing the reader beyond this unspeakability. I make this statement because Denise Duhamel’s Smile! makes this process feel so tangible to me.

In Smile!, Duhamel writes a book of poems in a trio of sections wherein the first two read more historically rooted through gender and references to location, and the final section, “Smile!”, turns into the expansion beyond reference; moving toward unspeakability, and then placing beyond. This book approaches the stories of grief & abuse & yearning to resolve one’s loneliness. From the continual reminders of lovers and friends being afflicted or falling to AIDS to the omnipresence of masculinity, that bulky weakness, which stalks her speakers & presses into any domain of authority within their lives.

Many approaches to these concepts — trauma, grief — feel very vulnerable and inquisitive in the writer and speaker’s attempts for understanding. What surprises me with Duhamel, though, is on first reading I did not think this book was very questioning — except for the following Boy George poem, none of the pieces seemed to really be searching for something — the trauma already seems understood. I went back and counted 32 questions through these 97 pages of poems. I don’t think my lack of observation in these poems was inattentiveness, but rather that the poems never seem to rely on a question to point toward unspeakability. This poem seems to write so specifically on unknowing or knowing or projecting or relating, “On Being Born the Same Exact Day of the Same Exact Year as Boy George”:

In the latest articles, Boy George is claiming he’s not

really happy. Hmm, I think, just like me.

when he comes to New York and stays at hotels in Gramercy Park

Maybe he feels a pull to the Lower East Side,

wanders towards places where I am, but not knowing me, doesn’t know why.

This book feels very in-the-head, psychoanalytic. Elizabeth Grosz, in her work Jacques Lacan: A Feminist Introduction, parses through a concoction of Freud, Kristeva, Lacan, Irigaray and other psychoanalysts to enable, what I find, to be a strong interpretation as well as digestible discussion on psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic impact on femininity and feminism. Grosz writes:

In short, the symbolic/oedipal/social mode owes a debt of existence to an unspeakable and unrepresentable semiotic/maternal/feminine. The symbolic cannot even acknowledge, let alone repay, the debt that the oedipal and the conscious owe to the pre-oedipal and the unconscious. This debt is the social equivalent of the debt the subject owes to a female corporeality which remains unrecognized in its autonomy.

I like to think about this moment, the symbolic debt to the feminine, with respect to another of Duhamel’s poems in this book. In “Kitchen,” she begins the poem,

I’m jealous when my mother touches anything else.

the potatoes that roll in the stainless steel sink.

the water runs and my mother rubs each bump —

under their chins, behind their necks — clean.

Sometimes she bathes me here, washes my hair

kneading small circles on my scalp. I trust her,

On one hand, readers are entering this poem through a very real moment of preparation, which feels like a central poetics for this book. On the other hand, the poems in Smile! are ripe with female figures and characters — coworkers, family members, friends, loves — who are all being documented with a similar stoicism towards traumas and abuses. The poetics of preparation is speaking towards how a female individual is equipped to handle the surrounding, future pain of their associates.

The final section feels more personal than the first two — she starts off with an experience of rape from a dentist. This section, and this book, sticks with me. Both took me some time to work through. I would go depressed reading it; not quite depressed in the sense that I’m blaming the book but more depressed in the sense of utter melancholy. Then there are poems which made me laugh through their cynicism? I add a question mark because I don’t think they’re truly cynical but I don’t have much of a better word to describe them. It’s cynical in the way that a self-deprecating joke is. Like a job interview where upon being asked what your strengths are you firmly answer No strengths, but people like to talk to me about their problems. I think of Duhamel’s poem, “Sometimes the First Boys Don’t Count”:

She was holding a wrench

to her lips. Your dad looked at me the same way you did,

but that was how I wanted to be looked at then--that was how

I thought it should be. You washed the grease from your hands,

wiped your brow with your forearm and were ready.

It is full of the trauma that many of her poems hold close, and yet through the pain I still find myself laughing at the familiar ineptitude of men, their griminess that if I sit with for too long disturbs me.

The reason why I bring up the psychoanalytic function of this book is because I read the following quote and immediately felt as though Duhamel and Grosz were directly in conversation here:

In so far as she is mother, woman remains unable to speak her femininity or her maternity. She remains locked within a mute, rhythmic, spasmic, potentially hysterical - and thus speechless body, unable to accede to the symbolic because 'she' is too closely identified with/ as the semiotic. 'She' is the unspeakable condition of the child's speech.

Duhamel seems to be actively fighting that unspeakable condition, while actively embodying that rhythmic, spasmic, and potentially hysterical mode.

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.