ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Reyes Ramirez is a Houstonian. In addition to having an MFA in Fiction, Reyes received the 2014 riverSedge Poetry Prize and has poems, stories, essays, and reviews (and/or forthcoming) in: Southwestern American Literature, Gulf Coast Journal, Origins Journal, The Acentos Review, Cimarron Review, riverSedge: A Journal of Art and Literature, Front Porch Journal, the anthology pariahs: writing from outside the margins from SFASU Press, and elsewhere. You can read more of his work at www.reyesvramirez.com.

August 29, 2017

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

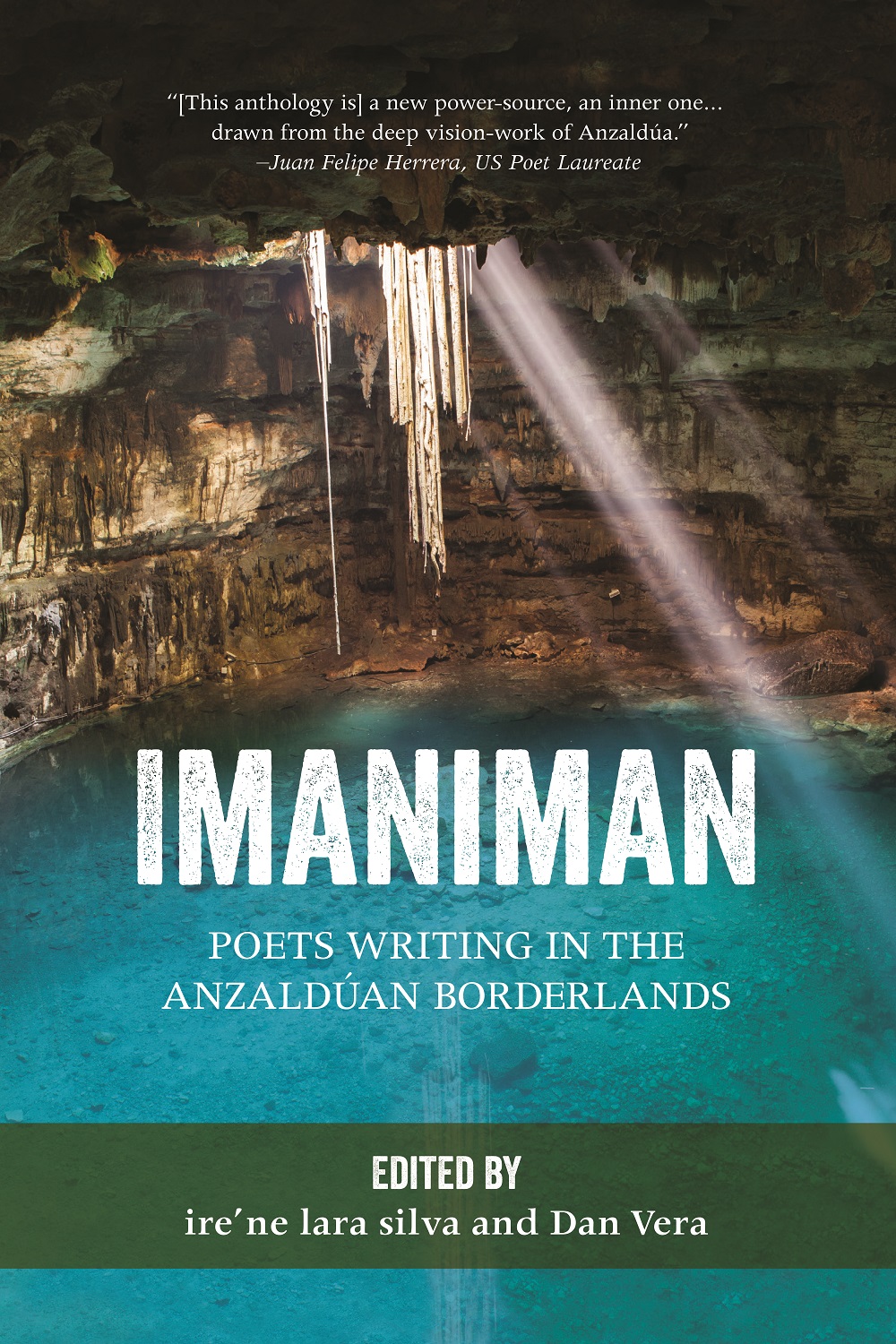

Review of Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera

Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands

Edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera

Aunt Lute Books, 2016

Growing up, I had to read, memorize, and be tested upon the mythology of European/Western civilizations. Even though I received my education in Texas schools (K-12, undergraduate, and graduate), I was never taught indigenous, Mexican, Chicanx, or borderland mythology, writers or theorists. I can't imagine what sort of writer or thinker I'd be today if I had studied Gloria Anzaldúa's seminal texts, ruminating, digesting, responding, criticizing, and growing from them. Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands (Aunt Lute Books, 2016, edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera) houses many writers who have done that work. It's why I can't stress how amazing this book is.

Former Poet Laureate of the United States Juan Felipe Herrera sets the tone with a poetically fluid introduction that breaks any sort of formal expectations you would have of an anthology. Again, as much as this collection is an homage Anzaldúa's writings, it's about showing the influence she's had on contemporary writers. One of Anzaldúa's ideas, out of many, is the ever-shifting nature of identity and thus, how humanity imbues everything with this nature despite, or in spite of, oppression imposed by hetero/patriarchal/capitalist/white supremacist guidelines. Writing is no different. Particularly, Herrera spits out these phrases that can't be any clearer as they are mind altering, such as, "let us dream-examine." Herrera doesn't want to give you answers insomuch as he wants you to think about pressing issues, asking poignant questions such as, "Which feels right? […] Belonging to the same-language group? […] Belonging in the same-color group or belonging in the same marginalized community group? Can you cross over?" Herrera relies on the contributors to provide their own responses.

Which brings me to the plethora of voices in this collection, a testament to silva's and Vera's editorial work. It's clear that the editors wanted to showcase the far-reaching influence Anzaldúa had on different communities across the US and the world. The concept of the borderlands is not a wholly Mexican-American experience, as mainstream conversations would have you believe. There's representation from Central & South American experiences with pieces from Melanie Márquez Adams (Ecuadoran American), Roy G. Guzmán (Honduran American), Gabriela Ramirez-Chavez (Guatemalan American), and Elsie Rivas Gómez (Salvadoran American), for example. There’s Native American and African American voices from D.M. Chávez and Alexis Pauline Gumbs, respectively (and out of many more). There's voices from Filipino American, Syrian American, and Indian American writers in Barbara Jane Reyes, Nadine Saliba, and Marie Varghese, respectively. Not to mention the vast display of LGBTQ voices that intersect with these identities, nationalities, and ethnicities. If we're going to have real discussions of borders and intersectional identities, we need voices from the many peoples who speak to them from real experiences. As Saliba puts it: “…I realized that my story did not begin in 1975 with the Lebanese war … Because we read the Palestinian story within the global narrative of colonial conquest, resistance and the struggle for justice, my story begins in 1492.” Ideally, this is as Anzaldúan as it gets.

In addition, if you want a primer on some of the greatest working writers in the Southwest today, you'll get that here with Joe Jiménez, Lupe Mendez, Rodney Gomez, Jennine DOC Wright, Veronica Sandoval, and Emmy Pérez. If you want an introduction to incredible Californian writers of color, there's Olga García Echeverría, Monica Palacios, Daniel E. Solís y Martínez, Minal Hajratwala, among so many others. Quite simply, there's much to learn and appreciate here and you'd be hard pressed to find a fresh anthology that offers so many voices of different backgrounds in one place. After all, aren't so many of us still healing from the open wounds of displacement, of suppressed/oppressed identity inflicted by colonialism and heteropatriarchal, white hegemony? I'm also tired of presses and editors saying they can't publish writers of color because there aren't that many or of any quality; this anthology is proof, out of many, that that claim has and always will be based on nothing.

However, this isn't to say that the work presented can only exist in the context of the anthology, as each piece in here is a gem in a treasure trove of great writing. One writer whose work I've read and come to love is Cecca Austin Ochoa, whose "dream-examination" in this collection astounded me: "The first time I slept with a girl, we were in the jungle … I fumbled into her orgasm, and she cried, isn't this a revolutionary thing?" Simply gorgeous. I had several "Holy sh—" moments in what I was forced to realize from the works. Joe Jiménez has this haunting line: "Because fear is not an accident." jo reyes-boitel blew me away with an opening like: "I never fully invited the ghost / carried from generation to generation …” Same with Inés Hernández-Avila: "I have always moved among worlds, / I have never known otherwise." And Nia Witherspoon's first-person poem regarding the fractured nature of freedom on the individual fighting against prescribed identities: "maybe a little broken. / but free." There's even some flat-out realizations that come to light, such as in Tara Betts' essay: "While more people of color are getting graduate degrees, educational systems are eliminating tenure and increasing numbers of overextended adjuncts." There's just so much in this collection (and so many awesome voices I didn't mention.)

Ultimately, this anthology provides an important update to the conversation developed by Anzaldúa's Borderlands/La Frontera. If you've never read any of Anzaldúa's work, you'll get "dream-examinations" of her legacy that demonstrates what contemporary writers took most from her many ideas and contributions to queer/Chicanx/borderlands discourse. If you know and love her, you'll get new stories, interpretations, and works that she no doubt would be proud to have inspired. Either way, you can't go wrong. This is the anthology that dares to have Anzaldúan discourse without the limitations of formal, academic language and harmful, institutional guidelines of what constitutes "legitimate" conversations regarding borderlands, intersectionality, and sex. It's what we need.

Visit Aunt Lute Books' Website

Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands

Edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera

Aunt Lute Books, 2016

Growing up, I had to read, memorize, and be tested upon the mythology of European/Western civilizations. Even though I received my education in Texas schools (K-12, undergraduate, and graduate), I was never taught indigenous, Mexican, Chicanx, or borderland mythology, writers or theorists. I can't imagine what sort of writer or thinker I'd be today if I had studied Gloria Anzaldúa's seminal texts, ruminating, digesting, responding, criticizing, and growing from them. Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands (Aunt Lute Books, 2016, edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera) houses many writers who have done that work. It's why I can't stress how amazing this book is.

Former Poet Laureate of the United States Juan Felipe Herrera sets the tone with a poetically fluid introduction that breaks any sort of formal expectations you would have of an anthology. Again, as much as this collection is an homage Anzaldúa's writings, it's about showing the influence she's had on contemporary writers. One of Anzaldúa's ideas, out of many, is the ever-shifting nature of identity and thus, how humanity imbues everything with this nature despite, or in spite of, oppression imposed by hetero/patriarchal/capitalist/white supremacist guidelines. Writing is no different. Particularly, Herrera spits out these phrases that can't be any clearer as they are mind altering, such as, "let us dream-examine." Herrera doesn't want to give you answers insomuch as he wants you to think about pressing issues, asking poignant questions such as, "Which feels right? […] Belonging to the same-language group? […] Belonging in the same-color group or belonging in the same marginalized community group? Can you cross over?" Herrera relies on the contributors to provide their own responses.

Which brings me to the plethora of voices in this collection, a testament to silva's and Vera's editorial work. It's clear that the editors wanted to showcase the far-reaching influence Anzaldúa had on different communities across the US and the world. The concept of the borderlands is not a wholly Mexican-American experience, as mainstream conversations would have you believe. There's representation from Central & South American experiences with pieces from Melanie Márquez Adams (Ecuadoran American), Roy G. Guzmán (Honduran American), Gabriela Ramirez-Chavez (Guatemalan American), and Elsie Rivas Gómez (Salvadoran American), for example. There’s Native American and African American voices from D.M. Chávez and Alexis Pauline Gumbs, respectively (and out of many more). There's voices from Filipino American, Syrian American, and Indian American writers in Barbara Jane Reyes, Nadine Saliba, and Marie Varghese, respectively. Not to mention the vast display of LGBTQ voices that intersect with these identities, nationalities, and ethnicities. If we're going to have real discussions of borders and intersectional identities, we need voices from the many peoples who speak to them from real experiences. As Saliba puts it: “…I realized that my story did not begin in 1975 with the Lebanese war … Because we read the Palestinian story within the global narrative of colonial conquest, resistance and the struggle for justice, my story begins in 1492.” Ideally, this is as Anzaldúan as it gets.

In addition, if you want a primer on some of the greatest working writers in the Southwest today, you'll get that here with Joe Jiménez, Lupe Mendez, Rodney Gomez, Jennine DOC Wright, Veronica Sandoval, and Emmy Pérez. If you want an introduction to incredible Californian writers of color, there's Olga García Echeverría, Monica Palacios, Daniel E. Solís y Martínez, Minal Hajratwala, among so many others. Quite simply, there's much to learn and appreciate here and you'd be hard pressed to find a fresh anthology that offers so many voices of different backgrounds in one place. After all, aren't so many of us still healing from the open wounds of displacement, of suppressed/oppressed identity inflicted by colonialism and heteropatriarchal, white hegemony? I'm also tired of presses and editors saying they can't publish writers of color because there aren't that many or of any quality; this anthology is proof, out of many, that that claim has and always will be based on nothing.

However, this isn't to say that the work presented can only exist in the context of the anthology, as each piece in here is a gem in a treasure trove of great writing. One writer whose work I've read and come to love is Cecca Austin Ochoa, whose "dream-examination" in this collection astounded me: "The first time I slept with a girl, we were in the jungle … I fumbled into her orgasm, and she cried, isn't this a revolutionary thing?" Simply gorgeous. I had several "Holy sh—" moments in what I was forced to realize from the works. Joe Jiménez has this haunting line: "Because fear is not an accident." jo reyes-boitel blew me away with an opening like: "I never fully invited the ghost / carried from generation to generation …” Same with Inés Hernández-Avila: "I have always moved among worlds, / I have never known otherwise." And Nia Witherspoon's first-person poem regarding the fractured nature of freedom on the individual fighting against prescribed identities: "maybe a little broken. / but free." There's even some flat-out realizations that come to light, such as in Tara Betts' essay: "While more people of color are getting graduate degrees, educational systems are eliminating tenure and increasing numbers of overextended adjuncts." There's just so much in this collection (and so many awesome voices I didn't mention.)

Ultimately, this anthology provides an important update to the conversation developed by Anzaldúa's Borderlands/La Frontera. If you've never read any of Anzaldúa's work, you'll get "dream-examinations" of her legacy that demonstrates what contemporary writers took most from her many ideas and contributions to queer/Chicanx/borderlands discourse. If you know and love her, you'll get new stories, interpretations, and works that she no doubt would be proud to have inspired. Either way, you can't go wrong. This is the anthology that dares to have Anzaldúan discourse without the limitations of formal, academic language and harmful, institutional guidelines of what constitutes "legitimate" conversations regarding borderlands, intersectionality, and sex. It's what we need.

Visit Aunt Lute Books' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.