ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Rachel Mindell lives in Tucson and is the author of two chapbooks: Like a Teardrop and a Bullet (Dancing Girl Press) and rib and instep: honey (above/ground). She holds an MFA in Poetry and an MA in English Literature from the University of Montana. She serves as a Content Strategist for Submittable’s Marketing and Product Teams. Her poetry has appeared (or will) in DIAGRAM, Denver Quarterly, BOAAT, Forklift, Ohio, Glass Poetry, The Journal, Tammy, and elsewhere.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Insemination

December 13, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Meanwhile, Our Situation Has Been Upgraded to a “Situation:” One Poet’s Take on the Future Past

Radio, Radio

Ben Doller

Louisiana State University Press, 2001

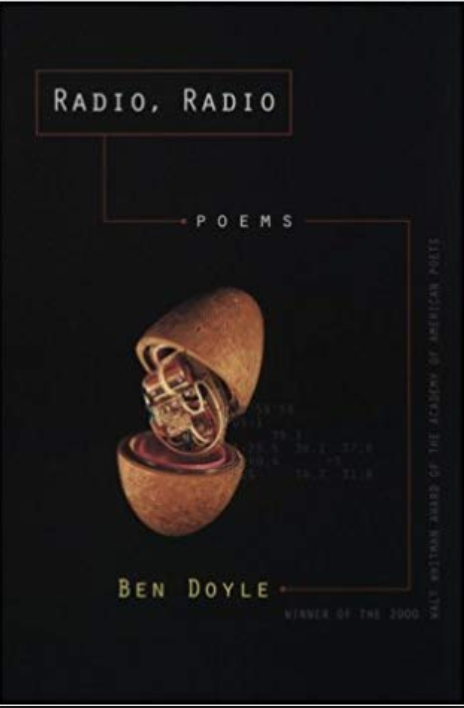

The cover of Radio, Radio (Louisiana State University Press, 2001) by Ben Doller (formerly Ben Doyle) depicts a man-made egg split open. Inside the egg, circuits and a battery are visible — outside the egg, data sets. This is the telemetric egg designed by George Stetten in 2001 to track nesting behavior among endangered birds at the Bronx Zoo, telemetric referring to the mechanism’s ability to record and transmit measurements. Devised inside a plastic Easter egg, the device contained sensors for temperature and gravity, a battery-powered transmitter, and an antenna. A larger, thicker, and more neutral-toned shell surrounds the plastic egg which allowed the device to succeed in relaying data about white-naped cranes the birds didn’t realize was fake.

Radio, Radio, selected by Susan Howe as the Winner of the 2000 Walt Whitman Award, is kin to the telemetric egg: experimental, intricate, inordinately clever, an advocate of preservation, and full of tiny, discrete wires. This book is an exquisite, impossible disguise; it’s surprising and smart and farcical and it relays messages that insist on repeated exposure to parse. And then how to read the figures and reassemble pieces to make use of the signal? The book begins:

This must be what I meant to tell you:

Nothing is nothing new, o my goddess, o my goodness.

the pandemonium fits on the head of a pin

whose body is within the body of a poisoned

poison red moth…

Make that a billion pandemoniums, each the size

of a panic… (1)

Ben Doller is an artist of the universe within a universe within an egg, on the verge of catastrophe and even after, wading through it with a wry smile. Indeed, it’s a challenge to read this book in the chaos of 2018 with enough empathy for the panic of 2001 when Radio, Radio was published, panic about technology, war, destruction of the natural world, pharmaceuticals, government, prisons, apocalypse, and scientific experiment among other anxieties.

Perhaps it’s hard because it’s too familiar and not enough of us did something when the early alarms sounded. Perhaps it’s hard because Doller evades the personal in favor of the collective, a style we’ve grown to distrust — there is indeed pain here and desire and plenty of human imperfection but the “I” and the “we” feel more archetypal and cinematic than candid. This is not a critique: given the distance from which you and I, in contemporary life, must interpret the signals and reach across the circuits toward one another, how else could it be? How else to take on the jumble that is (was) (will be?) life on Earth than with a little scientific detachment, a fair bit of wordsmithing, and a good dose of dark humor.

From “City Ledger” (31),

So these are the publicity shorts of our personal savior. And here is the residue’s

residue, & the list of twenty-seven miracles that happened to the eighth & least

Conspicuous ocean. Which is in this canister…

From “Re: Animation” (40),

Everything being identical, we are the idiots

& also their song. Camouflaged

Against the sky, against the sound.

The solid sound laps the shore, somewhat silent.

We are that song: a sibilance, a sigh…

Having made my own journey as a writer (from narrative poetry to despising narrative poetry to sheepishly reconsidering narrative as perhaps not always sentimental or confessional or elementary), I now find myself suspicious of the less personal verse, of the highly-crafted craft. This is both my own baggage and a product of our time, of a push for poems that don’t require outside research or a secret knock.

I struggled with this book — I read it in January and loved it (so brilliant!), revisited it in February with mild derision (this is so 2000 and male and difficult!) and take it up again in August with curiosity and respect. I think people should absolutely read Radio, Radio so we can talk about it for the next thousand years covered in nuclear dust. There is so much faculty and wisdom here, it’s electric coming off the page. It’s terrifying and deeply true, even when it’s far out. And also, the poems are hard to get a handle on — if only I could be a crane on a telemetric egg, go back to my MFA when I got lost in sound and intellect and just said “fuck it” if it meant deeply to me or not.

But we can’t do that as poets, even when we fear the limits of our art. Radio, Radio points toward the futility of writing (the futility of humans!) and still manages not to quit. “Re: Animation” closes with the question: “Do you recall the coda, the night / evaporating inward from the edge of itself, / leaving only me (always the last to leave) / to clean it up, to clean it up the way a mime does?” I’m probably missing the poet’s point in trying to trace the untraceable and establish a geography in life’s mess of mesh:

From “Satellite Convulsions” (2),

Your bath is drawn & in it are drawn (sputniks & stars) maps

& charts with which to constellate your body. Connect the dots.

A little ladle with four handles — a tiny light strobes in a cup, in hot

Convulsions of distance, bleats of temporal ignorance, synapse of morse

But no code, blood but no pulse, the stream but no mouth or source.

In an interview with George Stetten about the telemetric egg Stetten says, “I was a little worried about the egg because it relies on tiny, very high-energy batteries. If they short out, they blow up. I pictured accidentally blowing up a white-naped crane and what kind of headlines that would have made. Luckily, that never happened.” This feels like the sort of dangerous, comic, tragic outcome Doller would make great verse out of.

The book’s final poem, “Bottle in a Message in a Bottle; or Afterwords,” depicts a dystopia of darkness, tattooed lips, sore eyes, debris, ivy over glass, in which “something noxious blooms. After words broke beside / The Pool we threw them back, just to see. What is it” (71)? What dispatch do the words spell out, Radio, Radio? Are we still doomed? Is that funny?

Visit Louisiana State University Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.