ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Hannah Larrabee grew up on a blueberry farm in Maine, and somehow studied poetry with Charles Simic. Her full-length poetry collection, Wonder Tissue, won the 2018 Airlie Press Prize and will be released in September 2019. Her chapbook, Murmuration, is part of the Seven Kitchens Press series for LGBTQ poets. In 2016, Hannah was selected by NASA to see the James Webb Space Telescope in person and her poems were displayed at Goddard Space Center. She was recently awarded an Arctic Circle Residency in Svalbard, Norway. You can read more of her work on her website at hannahlarrabee.com or follow her on twitter.

May 21, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

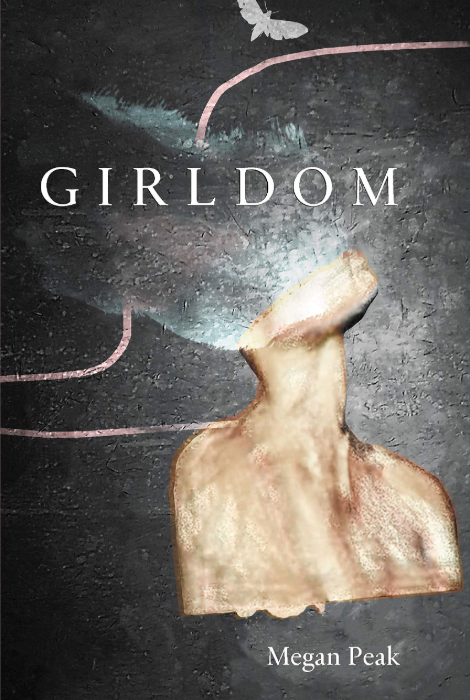

No Name for the Dark Inside a Tree: Review of Girldom by Megan Peak

Girldom

Megan Peak

Perugia Press, 2018

Megan Peak’s Girldom (Perugia Press, 2018) opens with a poem that becomes almost a sacrament, a shrine to the various incarnations of daughters. The diction is striking in this regard: pebbles, stone, salt, pearls, copper, gold—these are gifts of earth encapsulated in women. Yet, among daughters there are some who simply cannot be called luna (moon), who are not compelled by obligation, who will not be held by the nape.

Some women, saddled to the role of daughter and finding themselves always at an angle to that role, become searing moonscapes or “light from a dead / dead place.” Still, a daughter is light and so Peak’s work takes us through the boundless incarnations and vitality of women — once girls, always daughters, often wild, sometimes lovers, always curators of self, and always both prism and light.

What is remarkable about these poems is the dynamism of so-aptly-titled Girldom as opposed to the almost inanimate shrine a woman (her body) can become when held at arm’s length, when viewed from the lens of role, restriction, and objectification. Peak’s exploration teeters precariously between wild and restricted, rejecting lazy assumption. She is “the woman [she] continues to lose.”

The mood of these poems is similar to when you try to piece together the recollection of a vivid dream. There are brilliant poems to highlight, but for the sake of brevity (and because people should hold a copy in their hands) I think it best to be the stinging nettle Peak invokes. I’ll jump right to a moment I wish I had written, from the poem Insomnia: “sometimes when I can’t sleep / I peel oranges — and when I cry / I cry people — cities of them.”

Elusive is the fitting word for this collection, after all, how else is a woman to come to know herself in a world that so often forces experiences that bind her to her body? Her body must be open and closed, soft and hard; her body must become “unfold able — / a box and / another box,” just as her heart becomes “a heart within / a heart.” Peak’s poems charge into that territory of hurt without fear, and always with dignified and unique observation:

… It should matter

that I’m alive,

that I can jumpstart my own

halved heart. I’m not afraid of tenderness

or the bright belt of the sky

splitting across my face.

How is a woman to love when she must navigate a brutal world, darting back and forth, resting in fields, and not get caught … by what, by whom?

Another aspect of my admiration for Girldom is Megan Peak’s voice giving dimension to poems that already burst from the page. Her reading conveys an important ownership. Sometimes, a writer’s reading of a poem can be opposite to the voice one hears when reading from the page. There is no control to be had here, and I speak only from personal experience. I listened to Megan Peak read her poems first, then read from the collection. I’m glad I did, though reading Girldom certainly will not limit your indoctrination into the perilous world of embodiment, the wandering of it, the movement, impossibility, and beauty of girldom.

Visit Megan Peak's Website

Visit Perugia Press's Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.