ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Amorak Huey, a 2017 NEA Fellow, is author of the poetry collection Ha Ha Ha Thump (Sundress, 2015) and two chapbooks. He is also co-author with W. Todd Kaneko of the forthcoming textbook Poetry: A Writer's Guide and Anthology (Boomsbury, 2018) and teaches writing at Grand Valley State University. By way of disclosure, Porkbelly also published one of his chapbooks.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

The Kudzu, Everywhere

September 19, 2017

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

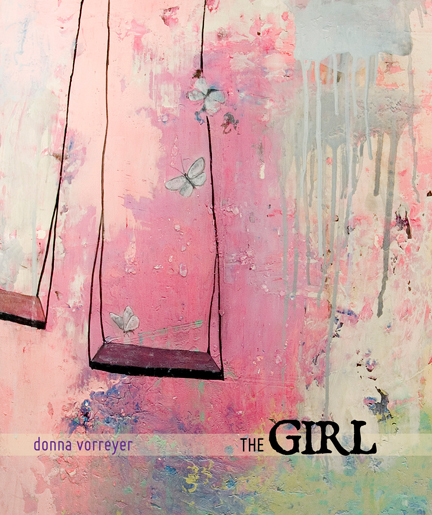

Review of The Girl by Donna Vorreyer

The Girl

by Donna Vorreyer

Porkbelly Press, 2017

There's a trend in recent years in crime fiction for novels to feature the word "girl" in the title. Think Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, etc. On the one hand, it's great to see the centering of the female experience; on the other hand, girl? Aren't all of these title characters women? There's something infantilizing about the word used in this way, a sense that the women in question are defined — and reduced — by the male gaze, by whoever makes marketing decisions in the publishing world. But of course "girl" is no insult, and Donna Vorreyer's The Girl (Porkbelly Press, 2017) makes sure we know that.

Vorreyer's new micro chapbook — consisting of eight prose poems that are at once searing and wistful — steps into this conversation by virtue of its title. The word is no reductive epithet in this case, to be sure. The experience being explored in this book is that of girlhood in America. Vorreyer, a middle school teacher in Illinois, dedicates the collection "To all the girls I have taught. To all the girls we once were." As this dedication suggests, there is nostalgia in these poems, and each poem seems to exist in a suspended temporality, bridging past, present, and future: "The girl goes to concerts only for encores, knows the group project will be done when she arrives. She's never flirtatious, just skips right to the sex and the goodbyes." The multitudes we contain are our various selves, Vorreyer suggests, the people we are or have been or will be all merging in every experience.

The book's title invites the reader to see the eponymous girl as archetype, offering one lens through which to read these poems. Many offer iconic details of girlhood — front-yard tea parties, playground swings, grade-school crushes — but in no cases are these stopping points or defining experiences. Rather, they are rites the girl passes through on the way to more complex and lyrical moments: "Instead she ties a bag of butterflies at her neck to feel their flapping wings against her chest. Instead she drinks the juice of twenty lemons and raises her arms as high as they can reach." There's a boundlessness to these poems, a clear promise that the girl's lived experience cannot be contained in these short paragraphs, cannot be pinned down by language. That's poetry, right? Using language to challenge language itself.

The titles of the poems are mostly adjectives — "Anachronistic," "Duplicitous," "Empathetic," "Fearless," "Holistic," "Scientific," "Wallflower," and "Tardy" — a list that itself suggests the complexity of being a girl, of being alive. It's unclear whether it's the same girl from poem to poem, and you could read it either way. That's part of the point, I think. One girl, eight girls, somewhere between. The poems both stand alone and work together; each girl is at once individual and universal: "Well-mannered, obedient, serious, shy, she drinks to fit in and smother her fear."

Appropriately, the prose itself is at times halting ("Fearless" interrupts itself with a series of parenthetical asides), at times rhythmic (as in the dactylic "embarrassed and awkward and clumsy at dancing"); the poems are full of such music: internal rhyme, assonance, consonance. The sentences are mostly short and often declarative — "When she sings, all the birds surrender. When she aches, she puts a stone beneath her pillow" — creating a kind of certainty, a straightforwardness, a trustworthiness. These are poems to be believed. This experience is real. Fraught and complex and contradictory and imaginative and impossible, naturally, but real nonetheless.

Like the crime novels mentioned earlier, Vorreyer starts this collection with a bit of a mystery, our heroic girl stopping "mid-stride in the center of a crosswalk." The world does not know what to make of her, frozen like this, getting in the way of things. The girl's parents, the police, a priest — all of them are unable to persuade her to move. The poem ends that way: the world freaking out, the girl unflinching.

Visit Donna Vorreyer's Website

Visit Porkbelly Press' Website

The Girl

by Donna Vorreyer

Porkbelly Press, 2017

There's a trend in recent years in crime fiction for novels to feature the word "girl" in the title. Think Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, etc. On the one hand, it's great to see the centering of the female experience; on the other hand, girl? Aren't all of these title characters women? There's something infantilizing about the word used in this way, a sense that the women in question are defined — and reduced — by the male gaze, by whoever makes marketing decisions in the publishing world. But of course "girl" is no insult, and Donna Vorreyer's The Girl (Porkbelly Press, 2017) makes sure we know that.

Vorreyer's new micro chapbook — consisting of eight prose poems that are at once searing and wistful — steps into this conversation by virtue of its title. The word is no reductive epithet in this case, to be sure. The experience being explored in this book is that of girlhood in America. Vorreyer, a middle school teacher in Illinois, dedicates the collection "To all the girls I have taught. To all the girls we once were." As this dedication suggests, there is nostalgia in these poems, and each poem seems to exist in a suspended temporality, bridging past, present, and future: "The girl goes to concerts only for encores, knows the group project will be done when she arrives. She's never flirtatious, just skips right to the sex and the goodbyes." The multitudes we contain are our various selves, Vorreyer suggests, the people we are or have been or will be all merging in every experience.

The book's title invites the reader to see the eponymous girl as archetype, offering one lens through which to read these poems. Many offer iconic details of girlhood — front-yard tea parties, playground swings, grade-school crushes — but in no cases are these stopping points or defining experiences. Rather, they are rites the girl passes through on the way to more complex and lyrical moments: "Instead she ties a bag of butterflies at her neck to feel their flapping wings against her chest. Instead she drinks the juice of twenty lemons and raises her arms as high as they can reach." There's a boundlessness to these poems, a clear promise that the girl's lived experience cannot be contained in these short paragraphs, cannot be pinned down by language. That's poetry, right? Using language to challenge language itself.

The titles of the poems are mostly adjectives — "Anachronistic," "Duplicitous," "Empathetic," "Fearless," "Holistic," "Scientific," "Wallflower," and "Tardy" — a list that itself suggests the complexity of being a girl, of being alive. It's unclear whether it's the same girl from poem to poem, and you could read it either way. That's part of the point, I think. One girl, eight girls, somewhere between. The poems both stand alone and work together; each girl is at once individual and universal: "Well-mannered, obedient, serious, shy, she drinks to fit in and smother her fear."

Appropriately, the prose itself is at times halting ("Fearless" interrupts itself with a series of parenthetical asides), at times rhythmic (as in the dactylic "embarrassed and awkward and clumsy at dancing"); the poems are full of such music: internal rhyme, assonance, consonance. The sentences are mostly short and often declarative — "When she sings, all the birds surrender. When she aches, she puts a stone beneath her pillow" — creating a kind of certainty, a straightforwardness, a trustworthiness. These are poems to be believed. This experience is real. Fraught and complex and contradictory and imaginative and impossible, naturally, but real nonetheless.

Like the crime novels mentioned earlier, Vorreyer starts this collection with a bit of a mystery, our heroic girl stopping "mid-stride in the center of a crosswalk." The world does not know what to make of her, frozen like this, getting in the way of things. The girl's parents, the police, a priest — all of them are unable to persuade her to move. The poem ends that way: the world freaking out, the girl unflinching.

Visit Donna Vorreyer's Website

Visit Porkbelly Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.