ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Anne Graue is the author of Fig Tree in Winter (Dancing Girl Press, 2017) and has work in SWWIM Every Day, Plath Poetry Project, Rivet Journal, Into the Void, Mom Egg Review, Random Sample Review, and One Sentence Poems. Her reviews have been published in Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Whale Road Review, The Rumpus, New Pages, and Asitoughttobe.com.

December 17, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

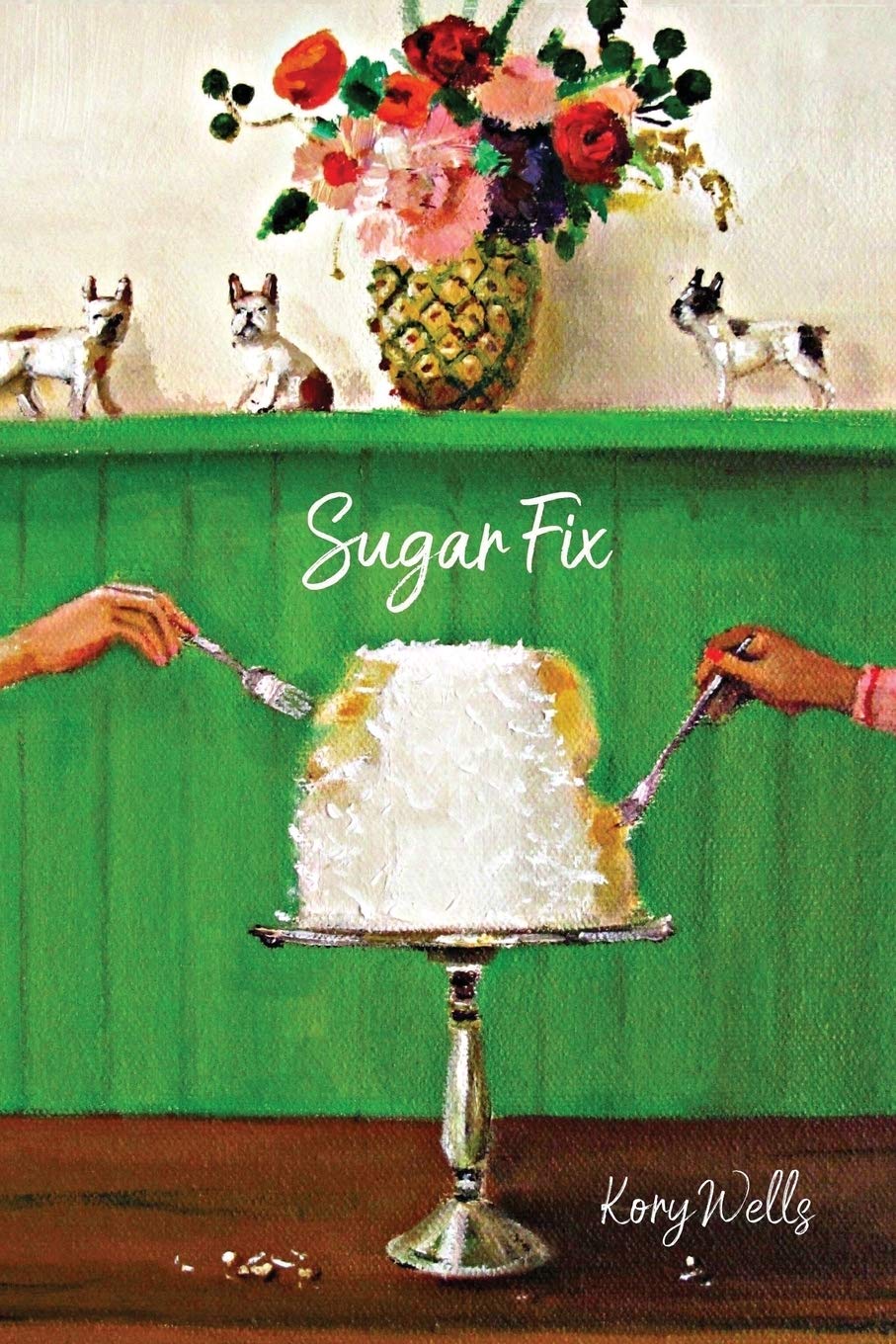

Review of Sugar Fix by Kory Wells

Sugar Fix

by Kory Wells

Terrapin Books, 2019

Kory Wells’ poetry collection, Sugar Fix (Terrapin Books, 2019), opens with “Dear Reader,” a sensual poem that offers a glimpse of what is to come. It draws the reader close with language as intimate as touch. What the speaker wants for them both is “a cozy room, // an amber bowl / of light, a sprinkle // of sugar across / the clear night sky.” It sounds wonderful and inviting in its short rhythmic lines as short as lovers’ breaths. After that, turning the pages is easy and urgent.

The first three poems in the first section of the collection are jewels of storytelling, sweet tastings of life from a speaker eager to make connections and savvy enough to discern saccharin from the real thing. In “He drove a four-door Chevy, nothing sexy, but I’d been thinking of his mouth for weeks” the speaker reveals her desire in the title, and we’re brought into that car riding along to the Dairy Queen with the “bright red logo faded like a movie star / who’s kissed away all her lipstick.” Even the mundane is sensual in this poem; the imagery does its job, breathing becomes a little more shallow and irregular. With these lines at the end of the penultimate stanza, a rope is pulled taut —

The bench seat

of his Chevy became a pew,

the space between us palpable

as the early summer humidity.

and the promise from the opening poem, of paradise, albeit tinged with apprehension, is realized.

The four poems that follow in the first section do not contain the same kind of imagery but instead focus on ancestors, family trees, DNA, relationships, and the self. In a section titled “Chocolate, Chocolate, Chocolate,” the shift in theme is noticeable. Instead of “a little taste of sugar” or standing at “the Winn Dixie checkout next to the gum and chocolate bars,” we are immersed in family history, a possible connection to Gypsy Rose Lee, (appealing in itself) and poems about uncertainty of identity and the earth. These poems are elegiac and a bit wistful. They also contain images that force us to notice our surroundings and contemplate who we are. At the end of the first section, things do feel uncertain—past, present, and future.

The second section promises “Layers of Rich Wonder,” and delivers in poems filled with marshmallow pies, bountiful desserts, and red velvet cake. “Postcards from the Cookie Jar” is a poem that mingles present and past for the speaker and her ancestors, mingles taste and a sweet tooth with slavery and colonialism. The speaker says, “We come from people who fed thin kids sugar / sandwiches,” easing pain, encouraging addiction to all things sugary and asks “What of the juju / of sugarcane, its slave trade, the might of something sweet?” noting that a sweet tooth comes at a high price.

The poem “Due to Chronic Inflammation” in the section titled “The Last Wedge of Apple Pie,” is an encompassing blend of imagery and allusion that communicates what is so difficult to say these days about how people feel about the state of the world in “a country where platitudes / grow thicker than roadside weeds.” Replete with references to mass shootings reported in Wikipedia and in Twitter feeds, the poem is a cry in the darkness where the speaker asks, “What can I do / but avoid sugar substitutes and shopping malls?” and then arrives at this:

I’m unlearning the urge for a sugar fix like I’m unlearning

my threshold for what is acceptable, terrible, commonplace.

The heat of this poem rises up from the page with words that seem to make sense in a reality that doesn’t and probably never will. It pleads, “Tell me I don’t have to unlearn hope.” Once again, the reader is in the conversation facing the daily barrage of lists, “the number of dead and injured.”

In each of the six sections of the collection, Wells has embedded the section title in a poem or selected the section title from a significant line or stanza. In either case the connection adds a cohesive link that tethers the poems together and conveys a communal essence, one that binds the sections together into an interconnected whole. There is a cadence in the progression from beginning to end, from free verse and prose poems to sonnets and elegiac tercets that helps to distill moments and memory, sweetness and pain.

And in the final section, “As I Already Said, Sugar,” the poems take on an other-worldly calm in a voice that is more self-assured and resilient. In a poem about death and rebirth, “There’s a God of False Starts and Tragic Mistakes,” the speaker says,

I will go to my grave wanting

to fly and sing like a bird.

Is it such a weakness

to come to a cold end

trapped in hope?

This harkens back to an earlier poem, “Unlike Emily’s,” in reference to Dickinson’s “Hope is the Thing with Feathers,” that likens hope to “a wild / and rowdy beast that crashes fencerow, charges / through the woods of her incessant wants…” that abandons the person in the poem who ends up searching for “ a solitary wren to follow home.” These and the other poems in Wells’ collection are reminders that “Some things are never right. / Some things are not better with time,” but we can find sanctuary sometimes in our small environments: we can look up and see “an astonishment of stars” or closer still, “a hundred / little windowpanes gauzed with tranquility.”

Visit Kory Wells's Website

Visit Terrapin Books' Website

Sugar Fix

by Kory Wells

Terrapin Books, 2019

Kory Wells’ poetry collection, Sugar Fix (Terrapin Books, 2019), opens with “Dear Reader,” a sensual poem that offers a glimpse of what is to come. It draws the reader close with language as intimate as touch. What the speaker wants for them both is “a cozy room, // an amber bowl / of light, a sprinkle // of sugar across / the clear night sky.” It sounds wonderful and inviting in its short rhythmic lines as short as lovers’ breaths. After that, turning the pages is easy and urgent.

The first three poems in the first section of the collection are jewels of storytelling, sweet tastings of life from a speaker eager to make connections and savvy enough to discern saccharin from the real thing. In “He drove a four-door Chevy, nothing sexy, but I’d been thinking of his mouth for weeks” the speaker reveals her desire in the title, and we’re brought into that car riding along to the Dairy Queen with the “bright red logo faded like a movie star / who’s kissed away all her lipstick.” Even the mundane is sensual in this poem; the imagery does its job, breathing becomes a little more shallow and irregular. With these lines at the end of the penultimate stanza, a rope is pulled taut —

The bench seat

of his Chevy became a pew,

the space between us palpable

as the early summer humidity.

and the promise from the opening poem, of paradise, albeit tinged with apprehension, is realized.

The four poems that follow in the first section do not contain the same kind of imagery but instead focus on ancestors, family trees, DNA, relationships, and the self. In a section titled “Chocolate, Chocolate, Chocolate,” the shift in theme is noticeable. Instead of “a little taste of sugar” or standing at “the Winn Dixie checkout next to the gum and chocolate bars,” we are immersed in family history, a possible connection to Gypsy Rose Lee, (appealing in itself) and poems about uncertainty of identity and the earth. These poems are elegiac and a bit wistful. They also contain images that force us to notice our surroundings and contemplate who we are. At the end of the first section, things do feel uncertain—past, present, and future.

The second section promises “Layers of Rich Wonder,” and delivers in poems filled with marshmallow pies, bountiful desserts, and red velvet cake. “Postcards from the Cookie Jar” is a poem that mingles present and past for the speaker and her ancestors, mingles taste and a sweet tooth with slavery and colonialism. The speaker says, “We come from people who fed thin kids sugar / sandwiches,” easing pain, encouraging addiction to all things sugary and asks “What of the juju / of sugarcane, its slave trade, the might of something sweet?” noting that a sweet tooth comes at a high price.

The poem “Due to Chronic Inflammation” in the section titled “The Last Wedge of Apple Pie,” is an encompassing blend of imagery and allusion that communicates what is so difficult to say these days about how people feel about the state of the world in “a country where platitudes / grow thicker than roadside weeds.” Replete with references to mass shootings reported in Wikipedia and in Twitter feeds, the poem is a cry in the darkness where the speaker asks, “What can I do / but avoid sugar substitutes and shopping malls?” and then arrives at this:

I’m unlearning the urge for a sugar fix like I’m unlearning

my threshold for what is acceptable, terrible, commonplace.

The heat of this poem rises up from the page with words that seem to make sense in a reality that doesn’t and probably never will. It pleads, “Tell me I don’t have to unlearn hope.” Once again, the reader is in the conversation facing the daily barrage of lists, “the number of dead and injured.”

In each of the six sections of the collection, Wells has embedded the section title in a poem or selected the section title from a significant line or stanza. In either case the connection adds a cohesive link that tethers the poems together and conveys a communal essence, one that binds the sections together into an interconnected whole. There is a cadence in the progression from beginning to end, from free verse and prose poems to sonnets and elegiac tercets that helps to distill moments and memory, sweetness and pain.

And in the final section, “As I Already Said, Sugar,” the poems take on an other-worldly calm in a voice that is more self-assured and resilient. In a poem about death and rebirth, “There’s a God of False Starts and Tragic Mistakes,” the speaker says,

I will go to my grave wanting

to fly and sing like a bird.

Is it such a weakness

to come to a cold end

trapped in hope?

This harkens back to an earlier poem, “Unlike Emily’s,” in reference to Dickinson’s “Hope is the Thing with Feathers,” that likens hope to “a wild / and rowdy beast that crashes fencerow, charges / through the woods of her incessant wants…” that abandons the person in the poem who ends up searching for “ a solitary wren to follow home.” These and the other poems in Wells’ collection are reminders that “Some things are never right. / Some things are not better with time,” but we can find sanctuary sometimes in our small environments: we can look up and see “an astonishment of stars” or closer still, “a hundred / little windowpanes gauzed with tranquility.”

Visit Kory Wells's Website

Visit Terrapin Books' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.