ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Carla Sofia Ferreira is a poet and teacher from Newark, New Jersey. The daughter of first-generation immigrants from Portugal, she currently teaches English language development to immigrant students in the Bay Area. Her poems have found homes, recently or forthcoming, at Poets Resist — Glass Poetry; The Fourth River; Reclaim: An Anthology of Women’s Poetry; Crab Fat Magazine and others. She is currently teaching her cat, Moonshadow, how to play fetch. Find her on Twitter.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Crossing The Line

March 13, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

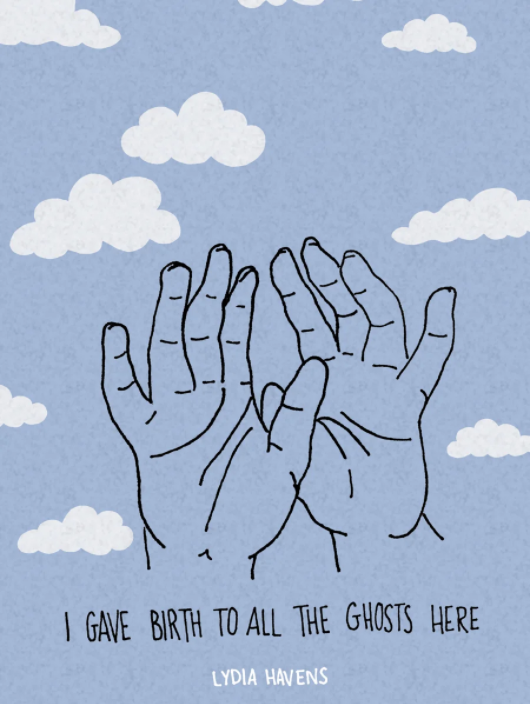

Review of I Gave Birth to All the Ghosts Here by Lyd Havens

I Gave Birth to All the Ghosts Here

Lyd Havens

Nostrovia Press, 2018

Content Warning: self-harm and suicide.

This book opens with a shout and ends with a photograph; throughout, Lyd Havens’ I Gave Birth to All the Ghosts Here, winner of the 2018 Nostrovia Chapbook Contest, focuses on what it means to be seen and heard in a society that continues to silence and make invisible those who are non-binary and those who are mentally ill. These two identities are explored thoughtfully and with exacting language: Havens’ ability to reveal beauty and mystery within painstaking attention to ugly realities calls to mind the poetry of Sandra Simonds and Lucia Perillo. But as Havens makes clear in their opening poem, “Invocation for my own voice,” they write with a voice that they have claimed as their rightful own: “Once, I wanted to stop having a body / and I guess now I have to be all voice.” To exist on these pages, not withholding their identity as nonbinary and mentally ill, is Havens’ resistance to the politics of silencing and invisibility.

Looking towards these politics, Havens doesn’t flinch as they wrestle with elders in the literary canon; fittingly, they place their clap-back poem to Billy Collins’ “Taking Off Emily Dickinson’s Clothes” immediately after their “Invocation for my own voice.” Collins’ misogynistic and creepy poem silences Dickinson, who obviously could not consent to the poem nor could she respond. He does so with ease as a white male poet and with little pushback; the response to this silencing of a woman poet was publication in Poetry’s February 1998 edition. Havens resists this rewriting (and silencing) of Dickinson’s narrative by enacting their own thought experiment with literary elder Ernest Hemingway in “Putting on Ernest Hemingway’s clothes.” What I love about their twist comes right away in the title: they do not focus on their undressing (the taking away), but the “putting on,” or the receiving. Havens is establishing themself in a literary tradition that still does not have its doors open to the gender-nonconforming. There is a complicated joy at work in the way they step into the clothes without permission:

The pants are a little loose.

I tell myself I’ll grow into them.

If I let myself grow into them —

into masculinity, or at the very least

androgyny, maybe then people

will remember my pronouns.

The looseness of the pants point to the many ways those of us who do not identify as male feel as though we do not fit in or have no place to exist as we are within the writing world. Look at the long history of women using pen names to appear male in order to be taken seriously or how nonbinary authors are consistently misgendered or how authors of color frequently see their names misspelled in print or mispronounced when spoken aloud. The pants do not fit! But Havens puts the pants on anyway in defiance of any claim that they do not belong there, in person and on the page. While “these fabrics / become the Gulf Stream” around them, Havens “learn[s] / how to swim.” This survival instinct is one that Havens takes from their personal life and integrates into their public identity as poet.

The personal reaches the physical in “Body as landscape as moon landing,” and shows the ways in which mental illness, public identity, and physicality intersect. A personal note before I delve further in: as someone with OCD that includes symptoms of dermatillomania, I had never before read a literary work that engaged with this aspect of it. To see Havens meaningfully write on it is an act of courage that left me feeling seen: it is this careful work that all their poems do, this seeing of and making seen what others might choose to turn away from. So it is in this poem, where physical scars are laid bare. The scars are not a metaphor and this poem dares you to look without pretending:

A lover stares at the small of my back

and asks about an accident. There are scars

on the insides of of my forearms that always

remind people of moon craters, and what July

I’ve made of my skin.

I love how Havens shows us the convenient ways others try to pretend away what is there; “an accident” or “moon craters” are other ways to not call them what they are: scars that we have given ourselves. This is work that is done with “hands [that] inevitably come back to me, / they’re always stained.” To suffer from dermatillomania is to create your own pain and scars, whether or not you want to. This poem, though, is also a creation of Havens’ hands and while they call their dermatillomania “A bloodoath / I can only make on my own,” I see their writing as a parallel form of bloodoath with opposite aims. Whereas dermatillomania is a type of self-erasure (to remove parts of oneself by compulsion) and a form of self-harm, poetry is an act of creation that in Havens’ hands becomes a way to exist on the page as they are, without erasure. To publish is the opposite of the invisibility that dermatillomania craves; with their “stained” hands, Havens uses this poem and others to make themself seen.

Ultimately, self-love becomes a path to survival in these poems, which we can see most prominently in Havens’ penultimate poem in the collection, “The act of loving myself is also an act of becoming.” This beautiful poem could be seen as an ode to self-love as nonbinary: in the first stanza, we see torn “floral / netted tights” that Havens “kept wearing.” In this way, they accept “[t]he frayed femininity” that they do not see at odds but as part of their identity as nonbinary. As they say in words I keep coming back to, “I / am finding comfort / in the stains and the unspooling […]” They ask frankly, “Isn’t it funny, / how being feminine / started feeling a lot more comfortable after / I came out as non-binary?” There is a delicious comfort here that Havens revels in, and an awareness of how this comfort has not come easy, even though now such existence feels “effortless.” The poet finally affirms that “Even / when I’m at my smallest, and angriest, / and most tired: I still become.” This “becoming” is a direct resistance against the unbecoming of mental illness, the silencing of nonbinary writers: it is creative, it is generative, it is life-affirming. From a poet who knows what it is like to not want to live and to not be seen, these words are hard-won.

In the final poem, “Ekphrasis on the first nude I ever took voluntarily,” Havens asserts their agency right from the very title. I want to note how self-harm is not a choice; to love yourself, however, is, and this is what this poem celebrates:

the lack of fear

in my eyes / there is no science to this /

but there’s a part of me that definitely

doesn’t understand it / I won’t argue

with the mirror / though / not today /

all the lights are humming my

favorite song / tonight I walk into

the current of my own body /

willingly—

Remember how earlier in “Putting on Earnest Hemingway’s clothes,” Havens showed us how they learned to swim? While then, they were attempting to survive in a space not made for them, here they are thriving in their own body; they are gliding in willing waters. Havens ends their exploration on overcoming invisibility with a photograph; most importantly, it is one they choose to take of their own body, a landscape that is their territory to name alone. I Gave Birth to All the Ghosts Here is a thoughtful wonder, and I hope this review has convinced you to add it to your shelf.

Visit Lyd Havens's Website

Visit Nostrovia Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.