ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Mariel Fechik lives in Chicago, IL and works in a library. She sings for the band Fay Ray and writes music reviews for Atwood Magazine and Third Coast Review. She is a Best of the Net and Bettering American Poetry nominee and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Hobart, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Cream City Review, and others. Her debut (micro)chapbook is due out August 2018 from Ghost City Press.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Gifted Bodies

September 11, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

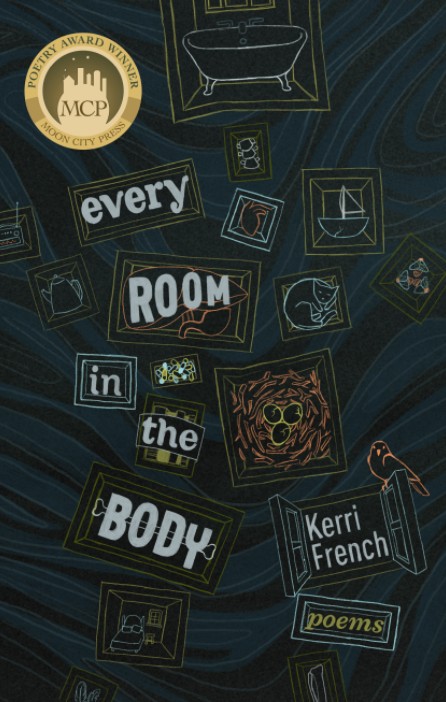

Review of Every Room In the Body by Kerri French

Every Room In the Body

by Kerri French

Moon City Press, 2017

“You’re told your baby will be/ born but maybe not alive.” “Diagnosis” comes seven poems into Kerri French’s debut, Every Room In the Body (Moon City Press, 2017). “Weeks fold in slow motion,” she writes, and we fold slowly along with her as she details an incredibly high-risk pregnancy in ways both dreamlike and starkly real. This is a book of contradictions, of intimacy and objectivity, of togetherness and alienation.

The book does not begin with diagnosis but with a fairy tale — or, rather, the pieces of one: “A knife. The loneliness of a forehead./ I spoke to my reflection in every mirror.” So begins a dream of a book in which even the real and heavy content becomes subject to surrealness. Poems like “The Doctor Asks Me When the Pain Began” start relatively straightforward: “Three days after my birthday/ while I sat in a theatre and watched/ a movie without sound.” But it, too, descends into a dreamlike state: “Eighteen,/ drinking vodka on the front lawn./ Waking from surgery/ in the wrong century.” There is at once a desire to disconnect from the present and to trace its lineage.

French’s poems are filled with the kind of minute detailed observation that often accompanies the deepest states of stress and anxiety, and yet, as Maggie Smith points out in her blurb, are “so controlled.” This control of language mirrors the speaker’s desire for control over the situation, her own body, or the external forces at work — all of which come to a head near the end of the book, in “Letting the Body Decide.” Referring to her unborn child, she writes, “My body, her captor.” This heartbreaking idea, that of pregnancy as danger rather than creation, reveals the truth of the speaker’s situation. Littered across the book, poems entitled “24 Weeks,” “27 Weeks,” “32 Weeks,” etc., demarcate the time with mounting tension and anxiety - as well as the disassociation that can accompany these emotions. The speaker of these poems seems to hover over them and be steeped within them simultaneously — in “Daytime Television, Late Night Sex”, the poem is written from first person perspective.

If this were a soap opera, the music would switch on

Before we made it to the bed, the lights would dim

Yet it reads voyeuristically, as though the speaker is floating near the ceiling, watching this scene unfold. In “The Doctor Asks Me to Describe the Pain,” French writes a series of sensory metaphors, each more visceral than the last. “Green eyes squinting in the sun,” and, “A train window/ slamming open, shut. Thirst of the chest.” She is both objective enough to describe the pain and so deep within it that the senses are the first thing to come to mind.

In “Apogee,” the speaker details a hospital room in which many women wait for news of their babies. At first, we feel the speaker has found a sense of community - others with which to feel together. But then she writes, “each of us pretending not to hear/ the other’s small whispers, how/ we cradled grief/ on the edge of our tongues/ until only the walls/ dared to answer.” Communal understanding might have been available, but each woman is so mired in her own body and experience that they cannot reach out to each other.

A repeated image that appears throughout the book is that of a bird’s nest, the mother coming frequently to feed the babies. In “Blue Feathers,” she writes of a dream in which the birds come to visit her at the hospital. In the end, they whisper to her, “We can save her, but we won’t.” A thread of fear and jealousy runs through each interaction with the birds, as though the birds parallel her situation completely. Even in poems in which the birds are absent, we see images of buried eggs, either by the speaker’s own hand or the doctors in “The Funeral Year.” Though these poems hold fear, they hold a shimmering well of hope as well. The speaker, who is both home and captor to her unborn child, remains buoyed by her daughter’s presence. And in the end, her daughter is there — “her lips so warm I almost forgot/ how she was nearly not here/ until she was.”

There is beauty and pain in abundance in Kerri French’s debut — a book to be absorbed slowly, for its beauty only becomes more potent with time.

Visit Kerri French's Website

Visit Moon City Press' Website

Every Room In the Body

by Kerri French

Moon City Press, 2017

“You’re told your baby will be/ born but maybe not alive.” “Diagnosis” comes seven poems into Kerri French’s debut, Every Room In the Body (Moon City Press, 2017). “Weeks fold in slow motion,” she writes, and we fold slowly along with her as she details an incredibly high-risk pregnancy in ways both dreamlike and starkly real. This is a book of contradictions, of intimacy and objectivity, of togetherness and alienation.

The book does not begin with diagnosis but with a fairy tale — or, rather, the pieces of one: “A knife. The loneliness of a forehead./ I spoke to my reflection in every mirror.” So begins a dream of a book in which even the real and heavy content becomes subject to surrealness. Poems like “The Doctor Asks Me When the Pain Began” start relatively straightforward: “Three days after my birthday/ while I sat in a theatre and watched/ a movie without sound.” But it, too, descends into a dreamlike state: “Eighteen,/ drinking vodka on the front lawn./ Waking from surgery/ in the wrong century.” There is at once a desire to disconnect from the present and to trace its lineage.

French’s poems are filled with the kind of minute detailed observation that often accompanies the deepest states of stress and anxiety, and yet, as Maggie Smith points out in her blurb, are “so controlled.” This control of language mirrors the speaker’s desire for control over the situation, her own body, or the external forces at work — all of which come to a head near the end of the book, in “Letting the Body Decide.” Referring to her unborn child, she writes, “My body, her captor.” This heartbreaking idea, that of pregnancy as danger rather than creation, reveals the truth of the speaker’s situation. Littered across the book, poems entitled “24 Weeks,” “27 Weeks,” “32 Weeks,” etc., demarcate the time with mounting tension and anxiety - as well as the disassociation that can accompany these emotions. The speaker of these poems seems to hover over them and be steeped within them simultaneously — in “Daytime Television, Late Night Sex”, the poem is written from first person perspective.

If this were a soap opera, the music would switch on

Before we made it to the bed, the lights would dim

Yet it reads voyeuristically, as though the speaker is floating near the ceiling, watching this scene unfold. In “The Doctor Asks Me to Describe the Pain,” French writes a series of sensory metaphors, each more visceral than the last. “Green eyes squinting in the sun,” and, “A train window/ slamming open, shut. Thirst of the chest.” She is both objective enough to describe the pain and so deep within it that the senses are the first thing to come to mind.

In “Apogee,” the speaker details a hospital room in which many women wait for news of their babies. At first, we feel the speaker has found a sense of community - others with which to feel together. But then she writes, “each of us pretending not to hear/ the other’s small whispers, how/ we cradled grief/ on the edge of our tongues/ until only the walls/ dared to answer.” Communal understanding might have been available, but each woman is so mired in her own body and experience that they cannot reach out to each other.

A repeated image that appears throughout the book is that of a bird’s nest, the mother coming frequently to feed the babies. In “Blue Feathers,” she writes of a dream in which the birds come to visit her at the hospital. In the end, they whisper to her, “We can save her, but we won’t.” A thread of fear and jealousy runs through each interaction with the birds, as though the birds parallel her situation completely. Even in poems in which the birds are absent, we see images of buried eggs, either by the speaker’s own hand or the doctors in “The Funeral Year.” Though these poems hold fear, they hold a shimmering well of hope as well. The speaker, who is both home and captor to her unborn child, remains buoyed by her daughter’s presence. And in the end, her daughter is there — “her lips so warm I almost forgot/ how she was nearly not here/ until she was.”

There is beauty and pain in abundance in Kerri French’s debut — a book to be absorbed slowly, for its beauty only becomes more potent with time.

Visit Kerri French's Website

Visit Moon City Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.