ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Sara Pisak is a graduate student earning her MFA in creative nonfiction from Wilkes University. She is employed as a Contributing Editor at Helen: A Literary Magazine and a freelance writer/editor. Sara participates in the Poetry in Transit Program and has recently published work in the Deaf Poets Society, Five:2:One Magazine, and Moonchild Magazine. When not writing, Sara can be found spending time with her family and friends. You can follow her writing adventures on Twitter: @SaraPisak10.

August 28, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

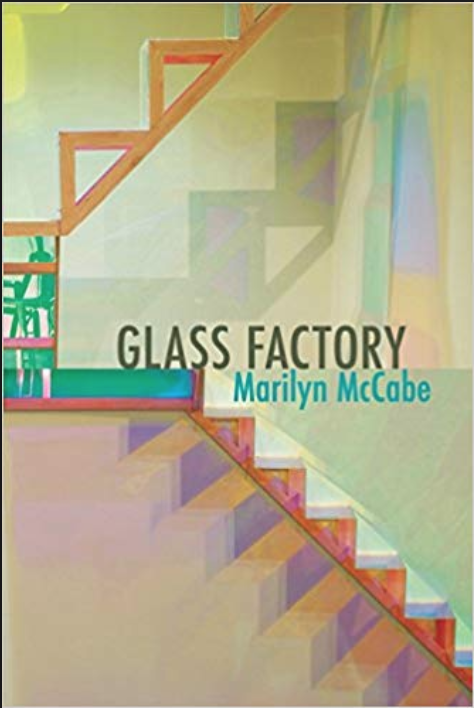

Review of Glass Factory by Marilyn McCabe

Glass Factory

by Marilyn McCabe

The Word Works, 2016

Marilyn McCabe’s Glass Factory (The Word Works, 2016) is an ode to the natural world and the void created from humanities’ transient interactions. These interactions with the planet create opportunities for self-discovery. The book’s title evokes glass and by extension, a lens, for which McCabe has carefully selected to present her work. This lens is fluid and rapidly changing. McCabe’s work, showing interactions and voids, echoes the fluid state of glass as well as the juxtaposing relationship between its properties: glass is both reflective and refractive, minimizing and magnifying, a solid and a liquid, opaque and transparent; and so is the Glass Factory.

Although Glass Factory has works which cover all the listed characteristics of glass, there is one characteristic which McCabe consistently employs: magnification. McCabe magnifies the natural world and in doing so magnifies the speaker’s understanding of him/herself. In her poem, “Remember Me,” McCabe writes:

The void behind. I drop

forward, drown. […]

Light ground as a lens,

to see, to see such small: o self.

In the water’s void, created by the speaker’s sinking body, the beaming sunlight breaks through the water’s surface creating a glass lens in which the speaker realizes just how minute their body, mind, and soul are in comparison to the natural elements of the world. In fact, Glass Factory’s primary exploration of identity is found in the idea that the only way to truly know oneself is through the microscopic lens in which the ebb and flow of collaborating with the world is the catalyst for discovery.

Another poem in this collection that uses the shifting characteristics of glass to magnify the self through environment interactions is “Glass Factory Ruin.” In this piece, McCabe’s speaker muses:

worker’s lunchtime toothpicks

will turn out to be a porcupine’s quills.

The act of remembering is itself a conjure.

Molten glass spun out over a plane […]

the world in the windowpane

shifts, as if itself melting toward rain.

My odd job: to reconstruct

what’s left behind, though it can cut.

Man-made myself, I’m on my knees

trying to find a little piece.

In magnifying the speaker’s understanding of self, McCabe again utilizes the shape shifting abilities of glass to explore what makes a person whole. This work features glass as molten, broken, intact, transparent, and murky. These contradictions in glass also reflect that the contradictions in people are what make them complete. As the speaker draws the conclusion that people are mosaics, the reader is also able to determine that embracing all facets of their being (like an ordinary piece of glass still retains all of its fluctuating properties) is the key to finding, what the speaker is searching for, the missing “little piece.” In this sense, as the glass is used to magnify properties of the self, which the speaker can investigate, the speaker and the glass become one.

Using the glass as the speaker’s persona, McCabe creates a collection which not only advocates self-introspection but also employs a keen eye for inspecting the world at large. As the two excerpts above illustrate, Glass Factory is filled with allusions to animals, to the day’s cycle, and to flora. These references and metaphorical links to the natural world range from “crows” to “crinoids” and “crepuscular animals” to “duckweed plants.”

Essentially, McCabe is asking the reader to consider the following: As the speaker interacts with these natural elements what can the reader learn about themselves? Put another way, what can the reader learn about their life as they look through the blurred lens of the duckweed or through twilight’s lens?

Glass Factory maintains through the speaker’s momentary interactions with nature that their humanity is changed both through interconnectedness with the natural world and the hollowness created when absent from these exchanges. Just like glass is recognizable in several states, so is the reader recognizable in the many facets of their lives.

Visit Marilyn McCabe's Website

Visit The Word Works' Website

Glass Factory

by Marilyn McCabe

The Word Works, 2016

Marilyn McCabe’s Glass Factory (The Word Works, 2016) is an ode to the natural world and the void created from humanities’ transient interactions. These interactions with the planet create opportunities for self-discovery. The book’s title evokes glass and by extension, a lens, for which McCabe has carefully selected to present her work. This lens is fluid and rapidly changing. McCabe’s work, showing interactions and voids, echoes the fluid state of glass as well as the juxtaposing relationship between its properties: glass is both reflective and refractive, minimizing and magnifying, a solid and a liquid, opaque and transparent; and so is the Glass Factory.

Although Glass Factory has works which cover all the listed characteristics of glass, there is one characteristic which McCabe consistently employs: magnification. McCabe magnifies the natural world and in doing so magnifies the speaker’s understanding of him/herself. In her poem, “Remember Me,” McCabe writes:

The void behind. I drop

forward, drown. […]

Light ground as a lens,

to see, to see such small: o self.

In the water’s void, created by the speaker’s sinking body, the beaming sunlight breaks through the water’s surface creating a glass lens in which the speaker realizes just how minute their body, mind, and soul are in comparison to the natural elements of the world. In fact, Glass Factory’s primary exploration of identity is found in the idea that the only way to truly know oneself is through the microscopic lens in which the ebb and flow of collaborating with the world is the catalyst for discovery.

Another poem in this collection that uses the shifting characteristics of glass to magnify the self through environment interactions is “Glass Factory Ruin.” In this piece, McCabe’s speaker muses:

worker’s lunchtime toothpicks

will turn out to be a porcupine’s quills.

The act of remembering is itself a conjure.

Molten glass spun out over a plane […]

the world in the windowpane

shifts, as if itself melting toward rain.

My odd job: to reconstruct

what’s left behind, though it can cut.

Man-made myself, I’m on my knees

trying to find a little piece.

In magnifying the speaker’s understanding of self, McCabe again utilizes the shape shifting abilities of glass to explore what makes a person whole. This work features glass as molten, broken, intact, transparent, and murky. These contradictions in glass also reflect that the contradictions in people are what make them complete. As the speaker draws the conclusion that people are mosaics, the reader is also able to determine that embracing all facets of their being (like an ordinary piece of glass still retains all of its fluctuating properties) is the key to finding, what the speaker is searching for, the missing “little piece.” In this sense, as the glass is used to magnify properties of the self, which the speaker can investigate, the speaker and the glass become one.

Using the glass as the speaker’s persona, McCabe creates a collection which not only advocates self-introspection but also employs a keen eye for inspecting the world at large. As the two excerpts above illustrate, Glass Factory is filled with allusions to animals, to the day’s cycle, and to flora. These references and metaphorical links to the natural world range from “crows” to “crinoids” and “crepuscular animals” to “duckweed plants.”

Essentially, McCabe is asking the reader to consider the following: As the speaker interacts with these natural elements what can the reader learn about themselves? Put another way, what can the reader learn about their life as they look through the blurred lens of the duckweed or through twilight’s lens?

Glass Factory maintains through the speaker’s momentary interactions with nature that their humanity is changed both through interconnectedness with the natural world and the hollowness created when absent from these exchanges. Just like glass is recognizable in several states, so is the reader recognizable in the many facets of their lives.

Visit Marilyn McCabe's Website

Visit The Word Works' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.